Effect of Intensive Patient Education vs Placebo Patient Education on Outcomes in Patients With Acute Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial

SOURCE: JAMA Neurol 2019 (Feb 1); 76 (2): 161–169

Adrian C. Traeger, PhD; Hopin Lee, PhD; Markus Hübscher, PhD; Ian W. Skinner, PhD; G. Lorimer Moseley, PhD; Michael K. Nicholas, PhD; Nicholas Henschke, PhD; Kathryn M. Refshauge, PhD; Fiona M. Blyth, PhD; Chris J. Main, PhD; Julia M. Hush, PhD; Serigne Lo, PhD; James H. McAuley, PhD

Neuroscience Research Australia,

Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

Sydney School of Public Health,

Faculty of Medicine and Health,

The University of Sydney,

Sydney, New South Wales, Australia.

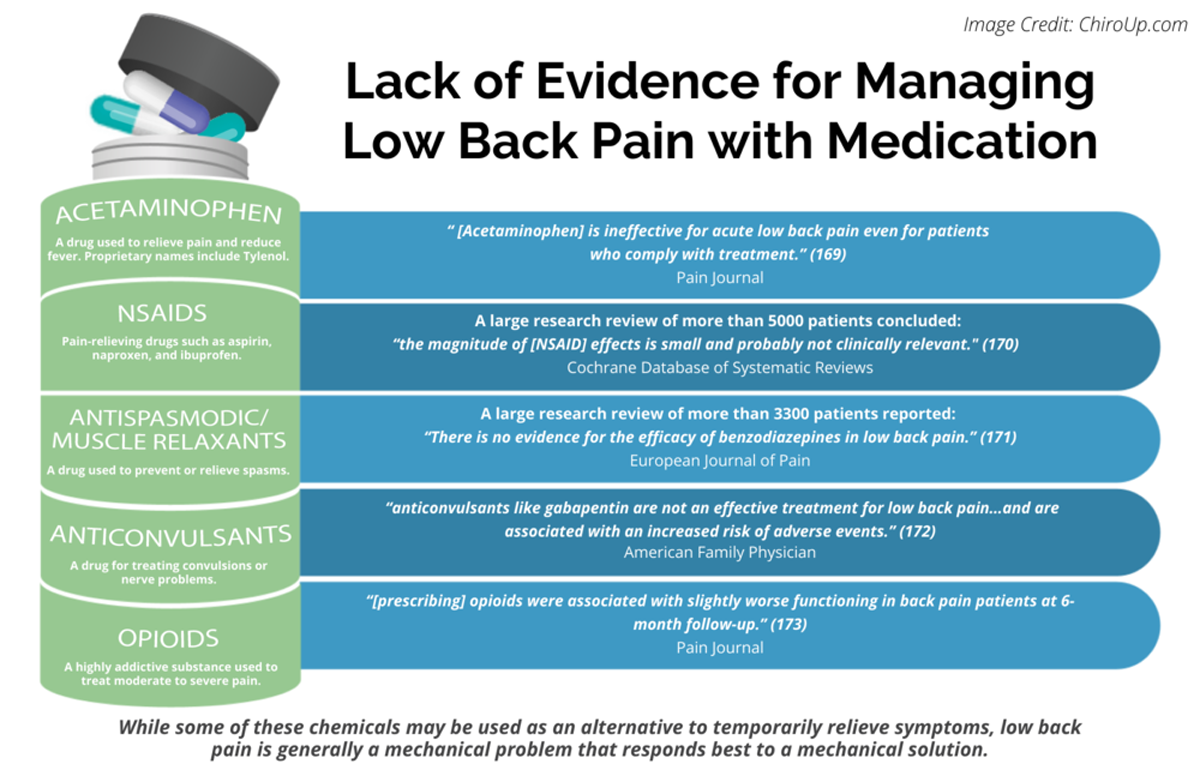

FROM: Pain 2019 (Dec)

FROM: Cochrane Database 2020 (Apr)

FROM: European Journal of Pain 2017 (Feb)

FROM: American Family Physician 2019 (Mar 15)

FROM: Pain 2013 (Jul)

Importance: Many patients with acute low back pain do not recover with basic first-line care (advice, reassurance, and simple analgesia, if necessary). It is unclear whether intensive patient education improves clinical outcomes for those patients already receiving first-line care.

There is more like this @ our:

LOW BACK PAIN Section and the:

Objective: To determine the effectiveness of intensive patient education for patients with acute low back pain.

Design, setting, and participants: This randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial recruited patients from general practices, physiotherapy clinics, and a research center in Sydney, Australia, between September 10, 2013, and December 2, 2015. Trial follow-up was completed in December 17, 2016. Primary care practitioners invited 618 patients presenting with acute low back pain to participate. Researchers excluded 416 potential participants. All of the 202 eligible participants had low back pain of fewer than 6 weeks’ duration and a high risk of developing chronic low back pain according to Predicting the Inception of Chronic Pain (PICKUP) Tool, a validated prognostic model. Participants were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to either patient education or placebo patient education.

Interventions: All participants received recommended first-line care for acute low back pain from their usual practitioner. Participants received additional 2 × 1-hour sessions of patient education (information on pain and biopsychosocial contributors plus self-management techniques, such as remaining active and pacing) or placebo patient education (active listening, without information or advice).

Main outcomes and measures: The primary outcome was pain intensity (11–point numeric rating scale) at 3 months. Secondary outcomes included disability (24–point Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire) at 1 week, and at 3, 6, and 12 months.

Results: Of 202 participants randomized for the trial, the mean (SD) age of participants was 45 (14.5) years and 103 (51.0%) were female. Retention rates were greater than 90% at all time points. Intensive patient education was not more effective than placebo patient education at reducing pain intensity (3–month mean [SD] pain intensity: 2.1 [2.4] vs 2.4 [2.2]; mean difference at 3 months, –0.3 [95% CI, –1.0 to 0.3]). There was a small effect of intensive patient education on the secondary outcome of disability at 1 week (mean difference, –1.6 points on a 24–point scale [95% CI, –3.1 to –0.1]) and 3 months (mean difference, –1.7 points, [95% CI, –3.2 to –0.2]) but not at 6 or 12 months.

Conclusions and relevance: Adding 2 hours of patient education to recommended first-line care for patients with acute low back pain did not improve pain outcomes. Clinical guideline recommendations to provide complex and intensive support to high-risk patients with acute low back pain may have been premature.

Trial registration: Australian Clinical Trial Registration Number: 12612001180808.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

For the past 5 years, the Global Burden of Disease Study [1] has consistently ranked low back pain as the leading cause of disability worldwide. Low back pain is second only to the common cold as a reason for consulting a general practitioner. [2] A recent international review highlighted a global crisis in the mismanagement of low back pain, with high rates of guideline-discordant care in both high- and low-middle income countries. [3–5] In their call to action, the Lancet Low Back Pain Series Working Group authors recommended that researchers and policy makers: “Develop and implement strategies to ensure early identification and adequate education of patients with low back pain at risk for persistence of pain and disability.” [3–5]

To manage uncomplicated acute low back pain (fewer than 6 weeks of pain duration), international guidelines recommend that general practitioners provide advice, education, reassurance, and simple analgesics, if necessary. [6] Although many patients receiving this care improve rapidly, 33% experience a recurrence in the next 12 months [7] and 20% to 30% develop chronic pain (defined as pain duration of 3 months or more). [8]

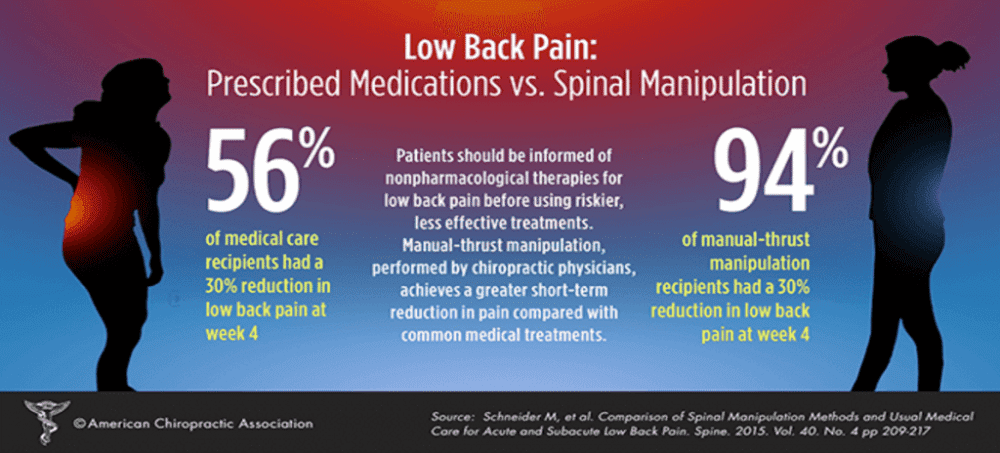

Patients who are at high risk of pain chronicity may require additional care, including second-line options such as physical (eg, spinal manipulation) and/or psychological therapies (eg, psychologically informed physiotherapy). [6] However, most trials that have evaluated adding second-line treatment options to standard guideline care for patients with acute low back pain have failed to demonstrate effectiveness compared with placebo (eg, addition of spinal manipulation, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or both [9]; addition of structured exercises [10]; and addition of acupuncture, massage, or chiropractic care [11]). Patient education, a treatment that authors of a 2008 Cochrane review [12] concluded was effective for acute low back pain when applied in an intensive format and that every major clinical guideline recommends (but with little instruction on intensity), [13] has never been tested in a placebo-controlled trial. Any benefits observed in previous trials of patient education for acute low back pain could be explained by nonspecific effects of the clinical encounter or the characteristics of the usual care comparison.

It’s impressive to see such a comprehensive study addressing the effectiveness of intensive patient education for those with acute low back pain. The findings challenge some widely held beliefs about patient education, emphasizing the need for a multi-dimensional approach to managing back pain. Notably, intensive patient education didn’t yield significant improvements over placebo patient education in pain intensity. This underlines that while education is essential, it might not be the ‘silver bullet’ for everyone, especially when considering the complexity of back pain and the myriad factors that can influence it.