Looking Ahead: Chronic Spinal Pain Management

SOURCE: Journal of Pain Research 2017 (Aug 30); 10: 2089–2095

Gregory F Parkin-Smith, Stephanie J Davies,

Lyndon G Amorin-Woods

School of Health Professions,

Murdoch University,

Perth, WA, Australia

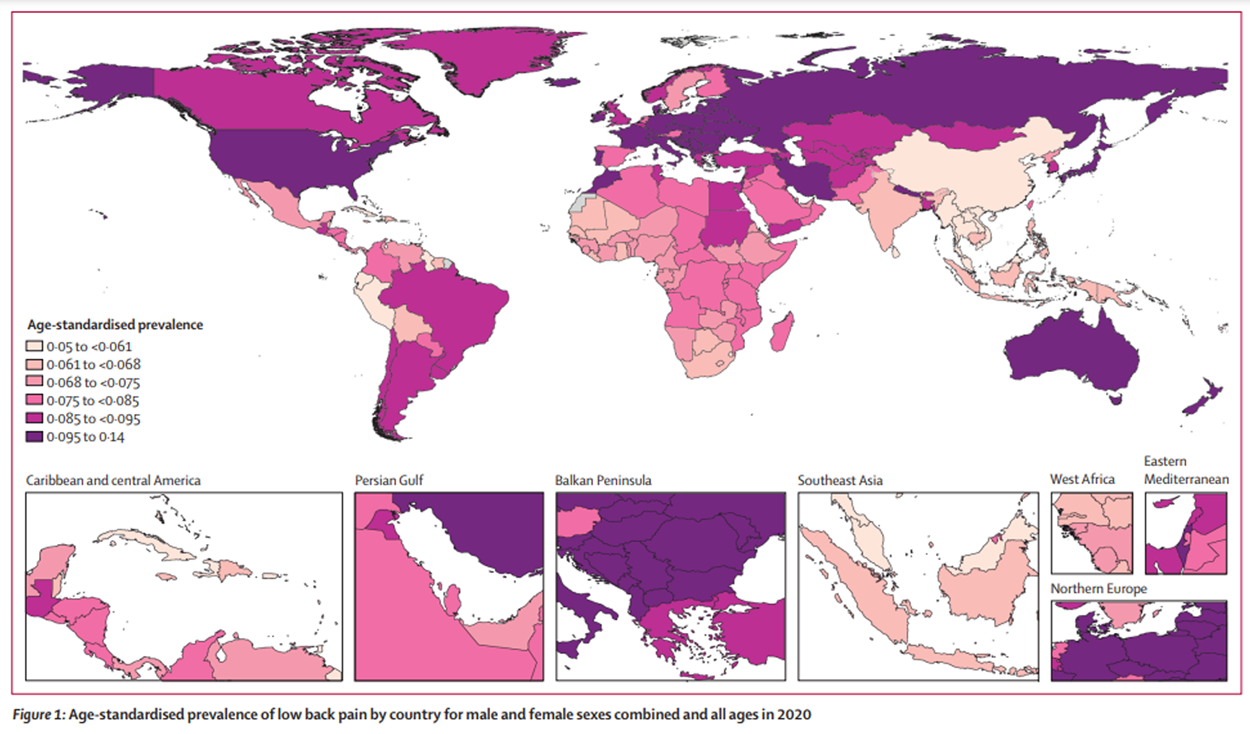

The other day, we oversaw a seminar on pain management for a local consumer pain group, where all consumers (patients) in attendance were experiencing chronic, persistent spinal pain. Each person had a unique story, and their experience and perceived cause of their pain differed. The quality of life in all these consumers was markedly reduced, which was the only clear similarity, confirming that there may be some similarities in the pain experience, but the pain experience was more often unique and individual. These consumers’ criticisms of care services were consistent, however, with dissatisfaction with their access to care and overall management of their pain. They described variable and often difficult access, limited continuity of care, they were often not taken seriously by health care providers, they received scant information about chronic pain and its prognosis and there were often noteworthy variations in the treatment they received. We agree that these criticisms are commonplace and a frequent gripe directed at health care practitioners about the “system.” [1] Moreover, the problems associated with care delivery are confounded by a number of patient/consumer factors, such as lifestyle habits, nutrition, body weight, depression, health literacy, geographical isolation and poor socioeconomic conditions, making the management of persistent pain even more complicated. [2] There is no doubt that, in the future, matching the care service and treatment with the individual patient will become an essential component of care services, as has been implied in published research. [3-6]

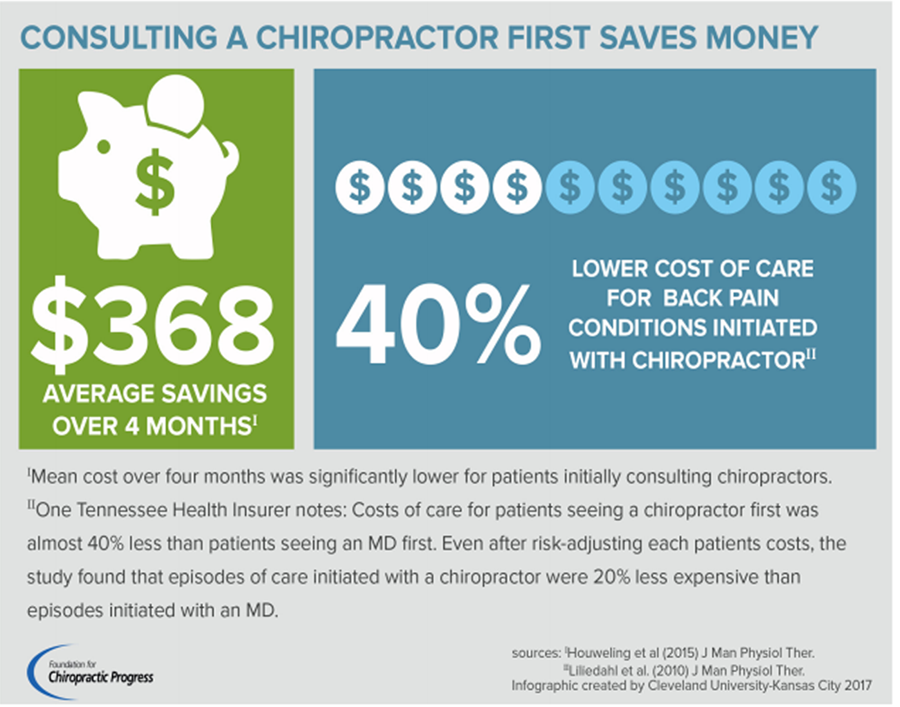

Health care practitioners involved in the triage and management of patients with persistent spinal pain will need to become more vigilant about individualizing and coordinating care for each patient, to achieve the best possible outcomes. For example, Cecchi et al concluded that patients with chronic (persistent) lower baseline pain (LBP)-related disability predicted “nonresponse” to standard physiotherapy, but not to spinal manipulation (an intervention commonly employed by chiropractors [7-9]), implying that spinal manipulation should be considered as a first-line conservative treatment. [9] We note that spinal manipulation is now suggested as the first-line intervention by Deyo, [10] since not a single study examined in a recent systematic review found that spinal manipulation was less effective than conventional care. [11]

Garcia et al, [12] conversely, showed that high pain intensity may be an important treatment effect modifier for patients with chronic low back pain receiving Mckenzie therapy (a treatment frequently used by physiotherapists). These examples demonstrate the importance of matching treatments with the characteristics of the patient.

There are more articles like this @ our:

Low Back Pain and Chiropractic Page

and the:

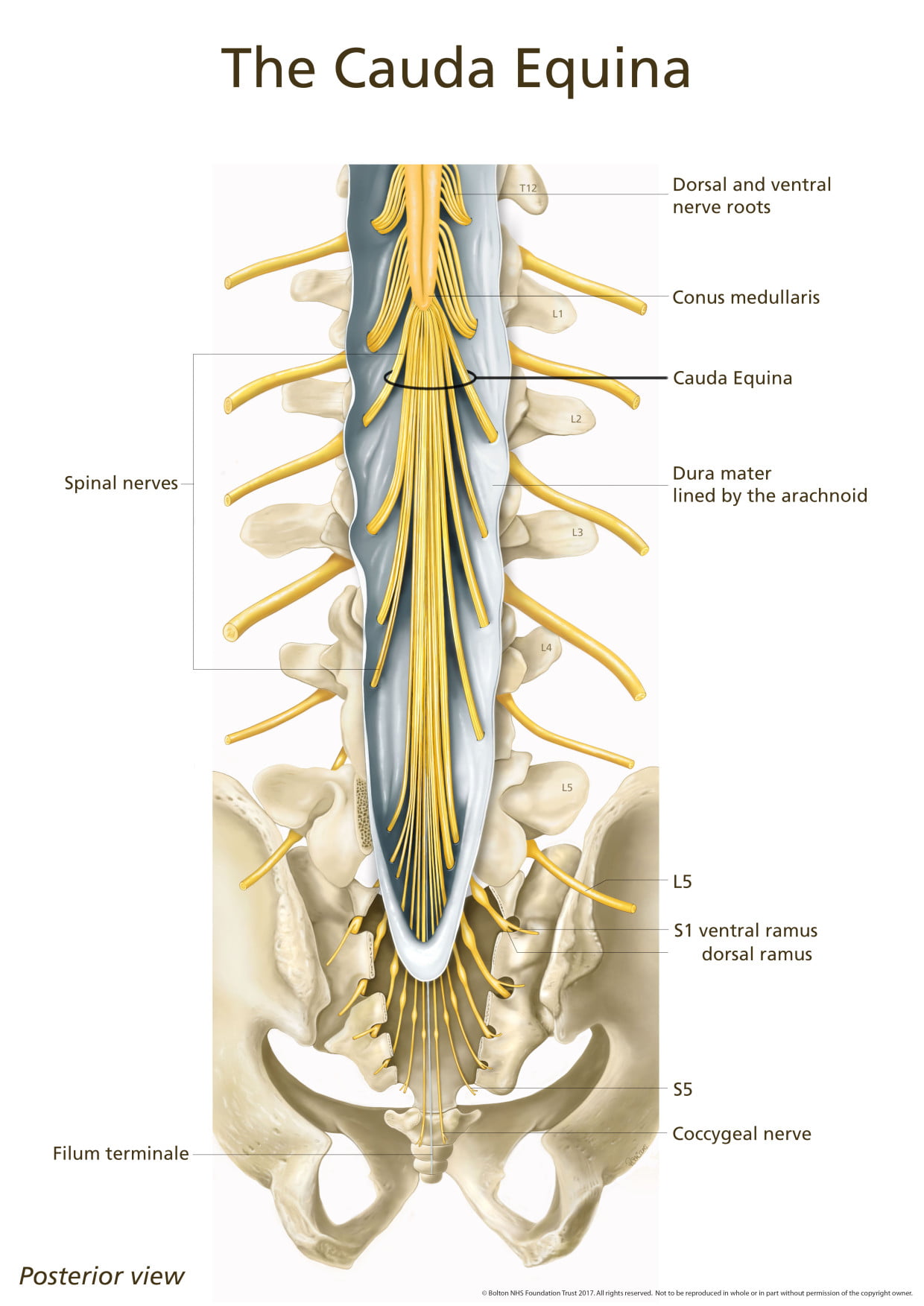

Similarly, identifying potential pain generators using diagnostic low-risk interventional pain procedures by precise anatomical instillation of local anesthetics informs the probability of subsequent therapeutic low-risk interventional pain procedures providing medium- to long-term pain relief for that individual. The potential to provide a therapeutic window, for months or years, can enable individuals to continue with evidence-informed behavioral change to achieve the patient’s short- and long-term goals. Interventional pain procedures are rarely performed in isolation because the procedure is only one part of a broader pain management plan.

The person in pain, prior to considering an interventional pain procedure, is ideally engaged in their own “prehabilitation,” which is the process of enhancing functional capacity of the individual to enable him or her to recover more quickly following a procedure. [13] We suggest that the sequence of interventions first involves patient assessment (history, examination, investigations, screening questionnaires, information from previous health care professionals), from which follows pain options that are relevant and available to the individual patient, which results in a pain management plan that is agreed and understood by both the patient (and their significant others) and treating practitioner and communicated to the other health care professionals (coaches). If a person in pain does not currently have a well-organized team providing evidence-based care, then their medical service will need to offer suggestions and coordinate local available options to form a virtual health care pain team. Figure 1 flow chart, is an example of the process of care service provision and the patient journey for the management of chronic spinal pain. Although interventional pain procedures have been utilized for many decades, it is not easy to find precise definitions. Specifically, the distinction between diagnostic and therapeutic procedures is often opaque, and so we have provided our definitions to reduce miscommunication between health care professionals (definitions are listed at the end of this article).

Read the rest of this Full Text article now!

Leave A Comment