Sports Management: Introduction to Sports-related Health Care

We would all like to thank Dr. Richard C. Schafer, DC, PhD, FICC for his lifetime commitment to the profession. In the future we will continue to add materials from RC’s copyrighted books for your use.

This is Chapter 1 from RC’s best-selling book:

“Chiropractic Management of Sports and Recreational Injuries”

Second Edition ~ Wiliams & Wilkins

These materials are provided as a service to our profession. There is no charge for individuals to copy and file these materials. However, they cannot be sold or used in any group or commercial venture without written permission from ACAPress.

Chapter 1: Introduction to Sports-related Health Care

If you were to ask the average coach about the responsibilities of an athlete, he would most likely reply that he or she was to conduct one’s self to the credit of the team, play fair, obey the officials, keep in training, be a credit to the sport, follow the rules, and enjoy the game: win or lose. This is the rhetoric commonly spooned to the naively inclined. If it were true, fewer sports injuries would be suffered.

With rare exception, even the Little Leaguer is commonly taught to WIN, drilled to disguise foul play from the eyes of the referees and umpires. Even in so-called noncontact sports, emphasis is often placed on getting the other team’s stars out of the game without causing injury to your own team. While conditioning is emphasized, the motivation is frequently on the preservation of a potential winning season rather than on prevention of a personal injury to a human being.

These words are harsh, but realistic. Yet, doctors handling athletic injuries must have a realistic appraisal of sports today if they are in good conscience to properly evaluate disability and offer professional counsel.

The Art of Evaluation

All people participating in vigorous sports should have a complete examination at the beginning of the season; and re-evaluation is often necessary at seasonal intervals. Re-evaluation is always necessary with cases where the candidate has suffered a severe injury, illness, or had surgery.

Evaluation begins with questioning. Because of drilled routine, any doctor is well schooled in the taking of a proper case history. But with an athletic injury, both obvious and subtle questions often appear. How extensive was the preseason conditioning? How much time for warm up is allowed before each game or event? What precautions are taken for heat exhaustion, heat stroke, concussion, and so forth? Does the coach make substitution immediately upon the first sign of disability for proper evaluation? How adequate is the protective gear? How many others on the team have suffered this particular injury this season?

Who, what, when, where, how, and WHY? These are the questions which must be answered before any positive course of health care can be extended. A detailed history of past illness and injury is vital. In organized sports, an outline of the regimen of training should be a part of the history, as well as a record of performance. Most sports will require a detailed locomotor evaluation of the player. Special care must be made in evaluating the preadolescent competitor because of the wide range of height, weight, conditioning, and stages of maturation. A defect may bar a candidate from one sport but not another, or it may be only a deterrent until it is corrected or compensated. Many famous athletes have become great in spite of a severe handicap.

The Physician’s Responsibilities

If a doctor only had to concern himself with injury prevention, care, and rehabilitation, his role would be much easier. But many other factors are inrvolved. For instance, consider motivation. The average coach has many pressures upon him, as do the players. These pressures may blind a coach to the fact that a player is participating with an injury, playing beyond the point of exhaustion, or playing with an injury where further trauma may lead to permanent injury. Players too, in their enthusiasm, may avoid reporting injury or even try to hide its effects.

The attending physician should mentally target that he is only responsible to the patient and his professional code of conduct. He is not responsible to the coach, trainer, ticket buyers, fans, school board, administrators, or the alumni association. Thus the question must be asked: Who has the authority to return an injured player to play or to practice: the physician, the trainer, or the coach? Obviously, no athlete should be allowed to risk permanent aggravation of an existing disability, regardless of the circumstance. In terms of pre-assessment before participation or competition, the physician should:

- Determine the fitness of the individual by a thorough history and examination relative to a particular type of activity, and, when necessary, arrange for evaluation and treatment. During the interview, take note of any prior injuries or weakness from prior competition. Each complaint should be checked thoroughly as some athletes have a tendency to be stoic. New team members should be carefully checked for pre-existing disorders that may compromise an athletic career. In addition, the physician and coach may wish to determine minimum standards of strength and fitness before letting someone participate.

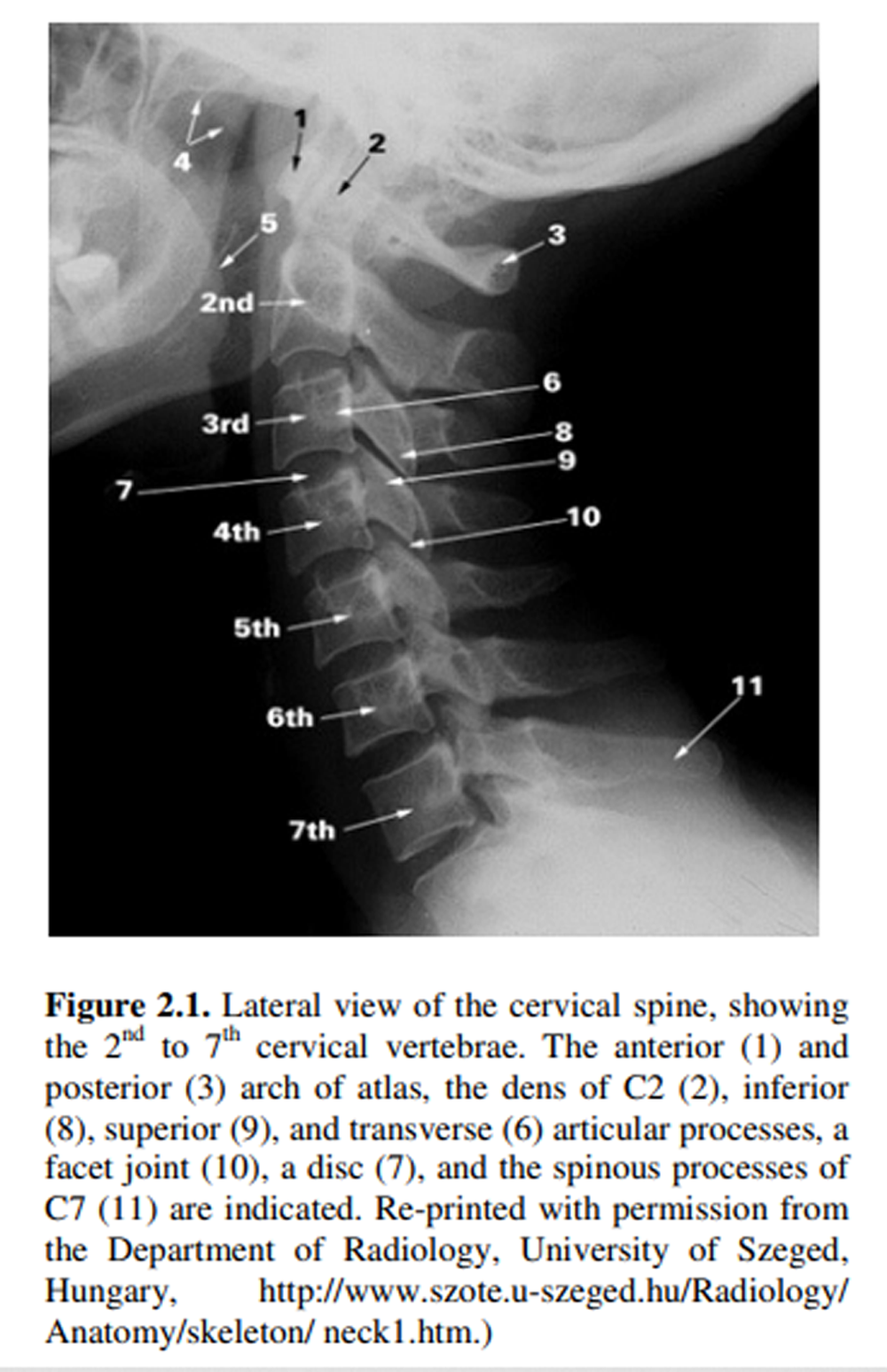

- Conduct basic clinical tests. A routine full blood count and urinalysis are essential, a standard resting ECG is often important, and a chest x-ray film is desirable. Comprehensive tests should always be taken when clinical symptoms or signs appear. The physical examination should always include a spinal analysis, posture check, and neurologic and orthopedic evaluation.

- Advise the candidate with an atypical condition of suitable sports or modifications. While all sports involve some risk, advise, or if necessary restrict, the candidate with overt or covert limitations from activities presenting great risk. Offer professional counsel which would contribute to optimal health and development.

- Consider a psychologic assessment as to the athlete’s goals, attitudes, desires, motivation, and reasons for participation. All physical, laboratory, and psychologic assessment tests must be made with the permission of parents or guardian in case of a minor.

Areas of Necessary Cooperation

The doctor must demand a degree of control equal to the responsibilities, and this is often difficult during the heat of competition. The physician’s decisions will not always be treated with respect by the nonprofessional. Thus, it is imperative that the doctor do his best in establishing areas of cooperation and an atmosphere of mutual rapport.

A sport is a game, and a game should not unduly jeopardize a person’s health or safety. However, the coach and the athlete justifiably expect both serious and minor disabilities to be treated with readiness, skill, and efficiency because any handicap has serious consequences. Both coach and athlete must feel that the doctor understands the problem and is as interested in returning the athlete to competition as they are. Honest, open communication is the cornerstone from which to build trust and confidence.

The Athlete

No rule exists that the athlete must confide in a doctor or accept his recommendations when there is a lack of confidence. The need for sympathetic understanding of the athlete and his particular problems and aspirations cannot be overemphasized. Creating an atmosphere of mutual confidence and trust is vital to establishing control. Likewise, the development of the athlete’s confidence in the doctor will help to prevent “doctor shopping” by the athlete to get the opinion the athlete wants. Without confidence in the doctor, the athlete may not report possible masking or harmful do-it-yourself or over-the-counter remedies or devices.

All disabilities are important, and all must be dealt with individually: not by rote or preference for a favorite “star” or influenced by pressures where each prediction of potential disability may be publicized. Each athlete presents a variance as to strength and weakness, attitudes, motivations and goals, pain threshold, development, body type, the specific acute trauma, etc. In a squad of two dozen, there are 24 unique people. These factors must be analyzed, differentiated, and a therapeutic solution applied.

The Trainer

The ego of a physician is often deflated when he learns that the trainer is held in higher respect. If a team had to choose between a team physician or a trainer, the physician would usually lose. And this respect is usually well earned. The trainer’s entire life has been devoted to the care of sports injuries. Loyalty also builds respect. Trainers have often been with the team for many seasons, while physicians have come and gone.

Many trainers and coaches possess a remarkable memory which can recall in detail a similar injury occurring many years ago, its efficient treatment, the exact duration of the rehabilitation process, and the capabilities of the athelete on recovery –to the dismay of a young doctor’s professional pride who must at least match the record.

While the trainer is commonly seen at the college and professional level, his aid is usually missing at the secondary and primary levels –and this lack makes the physician’s role overly demanding and sometimes impossible. The reason for this is that a trainer must be an expert at applying bandages, splints, dressings, slings, specialized athletic taping, and other first-aid measures. He is an expert at evaluating, ordering, fitting, and maintaining equipment, and is often called upon to custom design a special piece from available material. The skilled trainer is an expert in physical conditioning, physical rehabilitation, and in a large variety of physiotherapeutic applications and their contraindications. He must be knowledgeable in the risks of various field conditions: what constitutes a safe infield, turf, or track. And he must be knowledgeable in what an athlete will eat, regardless of nutritional theory and professional advice.

The trainer is often called upon to be squad psychologist, sociologist, counselor, friend, and confident. He serves as father confessor to the troubled athlete and is able to handle a large variety of temperaments and demands under pressure from both squad and staff. The experienced trainer “knows his people” for he lives daily with their complaints, hopes, opinions, personality quirks, and the unchecked locker room shop talk which few doctors are allowed to hear. He knows the art of listening to feelings rather than words and thus gains an insight of capabilities others do not have. This insight is invaluable to both physician and coach who do not enjoy the closeness with the athlete which the trainer is allowed.

A good trainer is more than an assistant to the doctor, he often serves somewhat as a mentor to the new team physician. On the other hand, an unskilled trainer must be carefully judged and evaluated as to capability of delegated duties and willingness to perform. Is there a definite plan for handling a serious injury or health emergency both at games and at practice? Planning ahead is imperative. Duties and procedures must be cordially discussed and mutally agreed upon, not proclaimed. The doctor and trainer have different yet parallel roles, and each should respect the experience and limits of the other. Few young doctors can tape a sprained joint as skillfully as an experienced trainer. The handicap of little mutual confidence is an impossible situation.

Care must be taken that the unskilled trainer does not allow numerous supplements, potions or pills, capsules or contraptions left unattended and available to an athlete to pick up at will. The administration of oxygen before or after exertion has no physiologic basis in increasing stamina or aiding recovery from fatigue.

Hirata reminds us that “The doctor who runs out on the field at the slightest provocation on heavily attended game days, but leaves the trainer to sink or swim during weekday practice, may impress the crowd and himself but certainly not the trainer or the team. Far worse, he exhibits little respect for the trainer’s integrity and in turn will receive very little.”

The Coach and Staff

As with the doctor-trainer relationship, the physician and coach have different yet parallel roles. The coach wants a winning team; the doctor wants a healthy team. Obviously, it is often impossible to “charm” an entire athletic staff or every athlete. Here lies the necessity of administrative power to cope with poor cooperation, else each disagreeable decision will be met with increasing subversion. While it is important to develop firm friendships with athlete, coach, and trainer, the doctor must take care that such cordial relationships do not cloud his professional principles.

| Review the complete Chapter (including sketches and Tables)at the ACAPress website |

Teams work is really the key ingredient. A nice balance of respect and expertise between the athlete , trainer and the physician will help boost athlete performances and lower injury.