Care for Low Back Pain: Can Health Systems Deliver?

SOURCE: Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2019 (Jun 1)

Adrian C Traeger, Rachelle Buchbinder, Adam G Elshaug, Peter R Croft, and Chris G Mahera

Institute for Musculoskeletal Health,

University of Sydney,

PO Box M179, Missenden Road,

Camperdown NSW 2050, Australia.

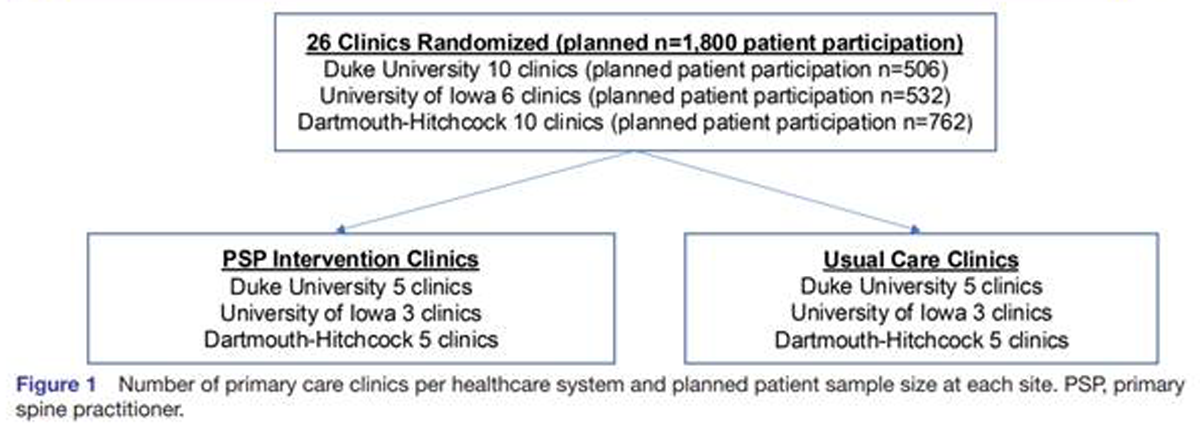

Low back pain is the leading cause of years lived with disability globally. In 2018, an international working group called on the World Health Organization to increase attention on the burden of low back pain and the need to avoid excessively medical solutions. Indeed, major international clinical guidelines now recognize that many people with low back pain require little or no formal treatment. Where treatment is required the recommended approach is to discourage use of pain medication, steroid injections and spinal surgery, and instead promote physical and psychological therapies. Many health systems are not designed to support this approach.

In this paper we discuss why care for low back pain that is concordant with guidelines requires system-wide changes. We detail the key challenges of low back pain care within health systems. These include the financial interests of pharmaceutical and other companies; outdated payment systems that favour medical care over patients’ self-management; and deep-rooted medical traditions and beliefs about care for back pain among physicians and the public. We give international examples of promising solutions and policies and practices for health systems facing an increasing burden of ineffective care for low back pain.

We suggest policies that, by shifting resources from unnecessary care to guideline-concordant care for low back pain, could be cost-neutral and have widespread impact. Small adjustments to health policy will not work in isolation, however. Workplace systems, legal frameworks, personal beliefs, politics and the overall societal context in which we experience health, will also need to change.

There are more articles like this @ our:

MEDICARE Page and the:

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Low back pain is the single biggest cause of years lived with disability worldwide, and a major challenge to international health systems. [1] In 2018, the Lancet Low Back Pain Series Working Group identified a global problem of mismanagement of low back pain. [2–4] The group documented the phenomenon of unnecessary care in both high- and low-income settings, whereby patients receive health services, which are discordant with international guidelines. [2–4] The articles summarized the strong evidence that unnecessary care, including complex pain medications, spinal imaging tests, spinal injections, hospitalization and surgical procedures, is hazardous for most patients with low back pain. [2–4]

Although we could not find systematic estimates for the worldwide prevalence of unnecessary care for low back pain, the CareTrack studies provide some indication of scale. Those studies estimated that 28% (95% confidence interval, CI: 19.7–38.6) of health care for low back pain in Australia (based on 164 patients receiving 6,488 care processes) [5] and 32% (95% CI: 29.5–33.6) of health care for low back pain in the United States of America (based on 489 patients receiving 4,950 care processes) [6] was discordant with clinical guidelines. The figures are likely an underestimate because they did not include diagnostic imaging tests. The upward trend in unnecessary care for low back pain is even more concerning. One meta-analysis from 2018 found that simple imaging tests were requested in one quarter of back pain consultations (415,579 of 1,675,720 consultations) and the rates of complex imaging (e.g. magnetic resonance imaging) had increased over 21 years. [7]

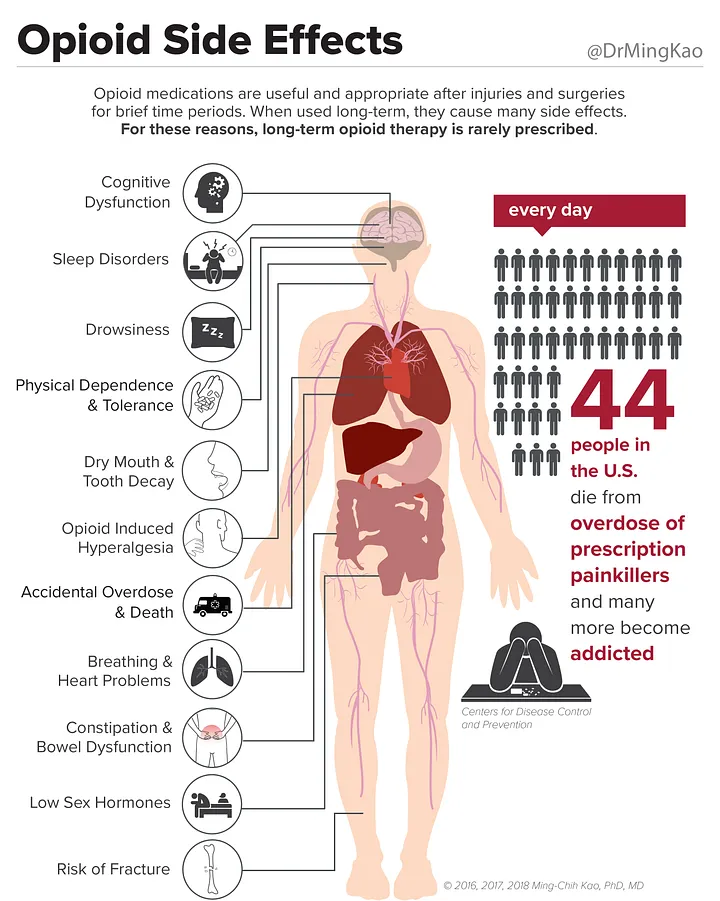

There is no robust evidence of benefit for spinal fusion surgery compared with non-surgical care for people with low back pain associated with spinal degeneration. [8] However, over the years 2004–2015, elective spinal fusion surgery in the United States increased by 62.3% (from 60.4 per 100,000 to 79.8 per 100,000), with hospital costs for this procedure exceeding 10 billion United States dollars (US$) in 2015. [9] In 2014, 3–4% of the adult United States population (9.6 million to 11.5 million people of 318.6 million) were prescribed long-term opioid drug therapy, in many cases because of chronic low back pain. [10] The Lancet working group called on the World Health Organization to increase attention on the burden of low back pain and “the need to avoid excessively medical solutions.” [4]

The movement away from medicalized management of low back pain is reflected in recent clinical guidelines. All six of the major international clinical guidelines released since 2016 prioritized non-medical approaches for patients with low back pain (Box 1). [11–16] Primary-care clinicians following these guidelines would manage uncomplicated cases with advice, education and reassurance. For patients at risk of developing chronic pain and disability, clinicians would, depending on which guidelines they followed, consider offering treatments such as spinal manipulation, massage, acupuncture, yoga, mindfulness, psychological therapies or multidisciplinary rehabilitation. Most health systems are not well-equipped to support this approach.

Read the rest of this Full Text article now!

Leave A Comment