Importance of the Type of Provider Seen to Begin Health Care for a New Episode Low Back Pain: Associations with Future Utilization and Costs

SOURCE: J Eval Clin Pract. 2016 (Apr); 22 (2): 247–252

Julie M. Fritz PhD PT FAPTA, Jaewhan Kim PhD, and Josette Dorius BSN MPH

Department of Physical Therapy,

College of Health,

University of Utah,

Salt Lake City, UT, USA.

| Editorial Comment

The RESULTS portion of this Abstract only partially discusses the findings, comparing 3 different professions’ treatment, costs, and outcomes for low back pain. In it they only mention the costs associated with medical management, while in reviewing chiropractic care vs. physical thereapy portions, they choose to emphasize:

That *seems* to suggest that physical therapy *may* entail less expense, or shorter durations of care, or that chiropractic patients are more likely to end up with surgery. None of that is true. Their own Table 2 plainly reveals that chiropractic care was the least expensive form of care provided to the 3 groups.

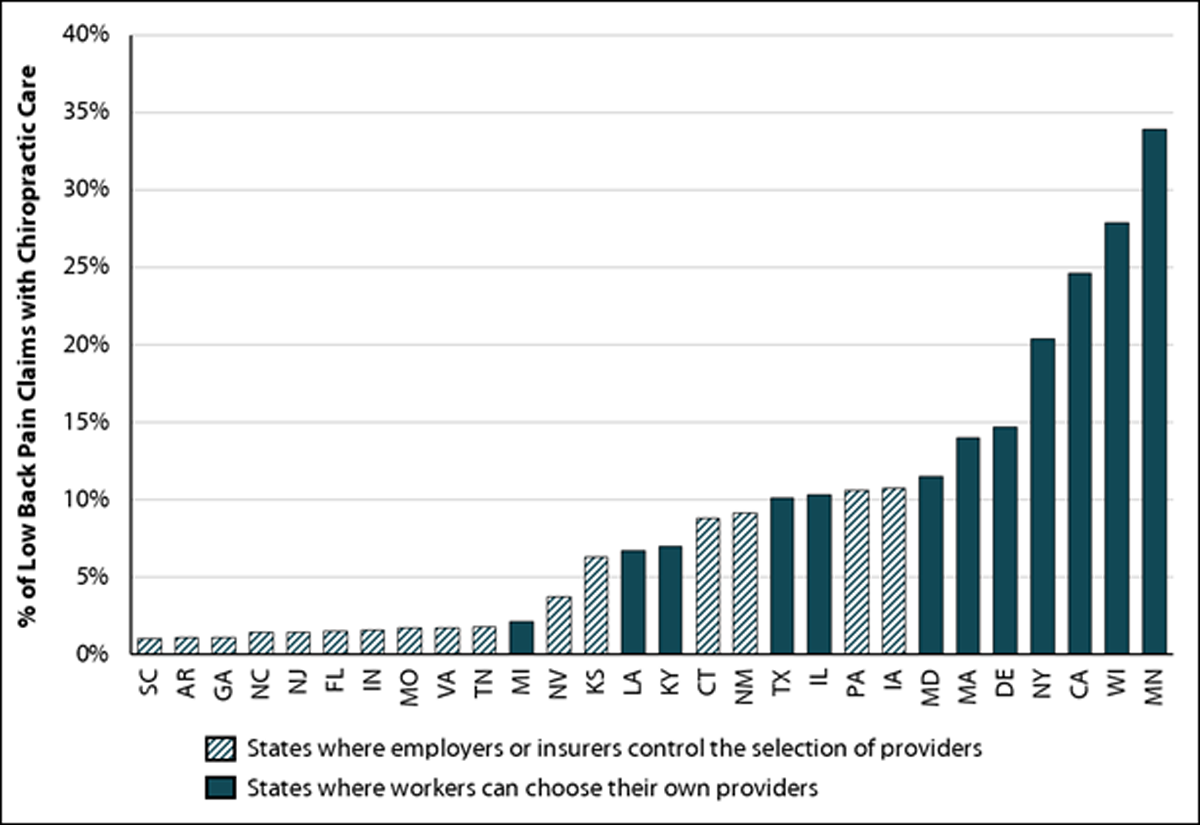

More recently Blanchette et al. [1] found, while reviewing 5,511 cases of workers who received compensation, that:

1. Association Between the Type of First Healthcare Provider In case you are wondering what’s bugging me, meta-analyses and other types of reviews always start by looking for Abstracts that fulfill their search criteria. This abstract does NOT suggest that chiroptactic is less costly (even though it was). Even more insultingly, in the DISCUSSION section, they slip in just a bit more deception:

Can you hear my blood boil yet? The proper terminology for a chiropractor is “Doctor of Chiropractic”, not a “non-doctor provider such as a physical therapist or chiropractor” Clearly they smell blood in the water. In the future, some profession WILL become the Gatekeeper for patients with low back pain, and this article tries to suggest that PTs should stand, hand-in-hand, with chiropractors in that doorway. I don’t think so. Chiropractors take almost 1000 hours of classes devoted spinal manipulation techniques, out of a 4,200 hour doctoral program. How many hours did they receive, and who did they receive it from? The University of Utah Department of Physical Therapy website does not say. Hmmm? |

RATIONALE, AIMS AND OBJECTIVE: Low back pain (LBP) care can involve many providers. The provider chosen for entry into care may predict future health care utilization and costs. The objective of this study was to explore associations between entry settings and future LBP-related utilization and costs.

METHODS: A retrospective review of claims data identified new entries into health care for LBP. We examined the year after entry to identify utilization outcomes (imaging, surgeon or emergency visits, injections, surgery) and total LBP-related costs. Multivariate models with inverse probability weighting on propensity scores were used to evaluate relationships between utilization and cost outcomes with entry setting.

RESULTS: 747 patients were identified (mean age = 38.2 (± 10.7) years, 61.2% female). Entry setting was primary care (n = 409, 54.8%), chiropractic (n = 207, 27.7%), physiatry (n = 83, 11.1%) and physical therapy (n = 48, 6.4%).

Relative to primary care, entry in physiatry increased risk for

radiographs (OR = 3.46, P = 0.001),

advanced imaging (OR = 3.38, P < 0.001),

injections (OR = 4.91, P < 0.001),

surgery (OR = 4.76, P = 0.012)

and LBP-related costs (standardized B = 0.67, P < 0.001).

Entry in chiropractic was associated with decreased risk for

advanced imaging (OR = 0.21, P = 0.001)

or a surgeon visit (OR = 0.13, P = 0.005)

and increased episode of care duration (standardized B = 0.51, P < 0.001).

Entry in physical therapy decreased risk of

radiographs (OR = 0.39, P = 0.017)

and no patient entering in physical therapy had surgery.

CONCLUSIONS: Entry setting for LBP was associated with future health care utilization and costs. Consideration of where patients chose to enter care may be a strategy to improve outcomes and reduce costs.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) impacts 60–80% of individuals at some in their lives. [1, 2] Management imposes a large socio-economic burden on health care systems. Total direct costs in the United States were estimated at over 86 billion dollars in 2005 [3] and costs related to LBP have been increasing at a rate faster than overall health care spending. [3, 4]

Given the prevalence of LBP it is not surprising that it ranks as the second or third most common symptomatic conditions for which an individual seeks health care. [5–7] An estimated one of every 17 doctor visits are attributable to LBP [6] across several specialties, and LBP is the most common condition encountered in physical therapy and chiropractic practices. [8–10] Considering the number of providers involved and the myriad management options, it is not surprising that care patterns for LBP are highly variable. [11–15] Fragmented and variable care for LBP contributes to high levels of guideline discordant management, overuse of expensive and invasive procedures, and continual cost escalations without accompanying evidence of improved outcomes. [16–18]

Research increasingly points to the importance of early care decisions and guideline adherence in the prognosis of patients with LBP who seek care. For example, ordering a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or prescribing opioids within the first weeks is associated with increased risk for persistent symptoms, work disability and high costs. [19–23] Less attention has focused on the earliest care decision made by a patient, the type of provider selected to begin care. This decision likely has important implications for the prognosis and costs associated with an episode of LBP care. [24] Numerous provider types including several doctor specialties, physical therapists and chiropractors may serve as the point of entry for an individual with LBP. More research is needed to explore the implications of beginning care with different providers.

Read the rest of this Full Text article now!

Leave A Comment