Clinical Biomechanics: Body Alignment, Posture, and Gait

We would all like to thank Dr. Richard C. Schafer, DC, PhD, FICC for his lifetime commitment to the profession. In the future we will continue to add materials from RC’s copyrighted books for your use.

This is Chapter 4 from RC’s best-selling book:

“Clinical Biomechanics:

Musculoskeletal Actions and Reactions”Second Edition ~ Wiliams & Wilkins

These materials are provided as a service to our profession. There is no charge for individuals to copy and file these materials. However, they cannot be sold or used in any group or commercial venture without written permission from ACAPress.

Chapter 4: Body Alignment, Posture, and Gait

With the background material offered in the basic principles of the musculoskeletal system, statics, dynamics, and joint stability, this chapter discusses how these factors are exhibited in body alignment and posture during static and dynamic positions.

Gravitational Effects

Improper body alignment limits function, and thus it is a concern of everyone regardless of occupation, activities, environment, body type, sex, or age. To effectively overcome postural problems, therapy must be based upon mechanical principles. In the absence of gross pathology, postural alignment is a homeostatic mechanism that can be voluntarily controlled to a significant extent by osseous adjustments, direct and reflex muscle techniques, support when advisable, therapeutic exercise, and kinesthetic training.

In the health sciences, body mechanics has often been separated from the physical examination. Because physicians have been poorly educated in biomechanics, most work that has been accomplished is to the credit of physical educators and a few biophysicists. Prior to recent decades, much of this had been met with indifference if not opposition from the medical profession.

Posture Analysis

It has long been felt in chiropractic that spinal subluxations will be reflected in the erect posture and that spinal distortions result in the development of subluxation syndromes. Consequently, an array of different methods and instrumentation has been developed for this type of analytical approach such as plumb lines with foot positioning plates to allow for visual evaluation relative to gravitational norms, transparent grids, bubble levels, silhouettographs, posturometer devices to measure specific degrees in attitude, multiple scale units to measure weight of each vertical half or quadrant of the body, and moire contourography.

OBJECTIVES

Such procedures yield useful information; however, there is a great deal of possible subjective error in the interpretation of findings. Regardless, recorded analyses of body alignment serve as a guide to a patient’s holistic attitude, structural balance or imbalance, hypertonicity, need for therapeutic exercises, habitual stance, postural fatigue, basic nutritional status, and they offer a comparative progress record.

EYE DOMINANCE

One source of analytical error which can be easily corrected is that of eye dominance. It is important to realize that the examiner’s peripheral vision is used for judging the body bilaterally. This is true in posture analysis as well as in the physical examination when, for instance, bilateral motion of the rib cage is assessed. If the examiner has a dominant eye, the reclining patient should be observed with the dominant eye over the midline of the patient’s body.

Test. An examiner may determine eye dominance by the following procedure:

- hold the index finger of the right hand at arm’s length directly in front of the nose at the level of the eyes.

- Place the tips of the left index finger and thumb to form a circle.

- Place this circle directly in front of the nose about elbow distance away.

- Sight the tip of the right index finger in the center of the circle using both eyes.

- Close the left eye to see if the right index finger stays in the center of the circle. If it does, the right eye is dominant.

- Close the right eye to see if the right index finger stays in the center of the circle. If it does, the left eye is dominant.

INSPECTION

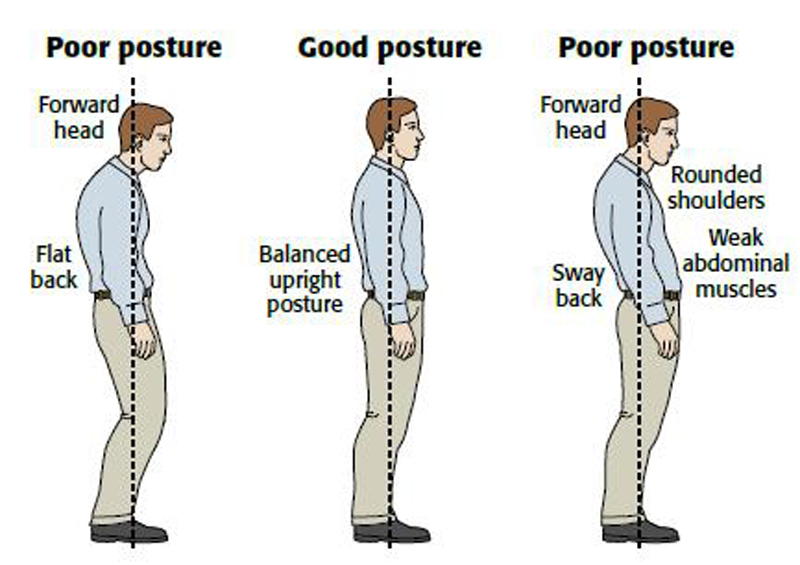

Have the patient stand with his heels together, with his hands hanging normally at his sides. Encourage the patient to stand normally and not try to assume “good posture” or the “military stance”. Note body type and then the following checkpoints relative to a lateral plumb line falling just anterior to the external malleolus (Fig. 4.1) and an anterior or posterior vertical line bisecting the heels.

Head and Neck. From the side, forward or backward shifting of body weight (not normal sway) can be judged by the position of the line from the ear. From the rear, note the position of the patient’s head by comparative ear level. If the head is tilted to the right, the chin will tilt to the left. Note the bilateral development of the sternocleidomastoideus and suboccipital muscles. Asymmetrical fullness of the suboccipital musculature indicates upper cervical rotation.

| Review the complete Chapter (including sketches and Tables) at the ACAPress website |

Feet are important to postural wellbeing. I work with a Chiro in my clinic to mutual benefit. Nice Blog. Thanks Stephanie