Implementation of the American- College of Physicians Guideline for Low Back Pain (IMPACt-LBP):

Protocol for a Healthcare Systems Embedded Multisite Pragmatic Cluster-randomized Trial

SOURCE: BMJ Open 2025 (Mar 26); 15 (3): e097133

Adam P Goode • Christine Goertz • Hrishikesh Chakraborty • Stacie A Salsbury • Samuel Broderick

Barcey T Levy • Kelley Ryan • Sharon Settles • Shoshana Hort • Rowena J Dolor, et al.

Duke University School of Medicine,

Durham, North Carolina, USA

Introduction: Low back pain (LBP) is a key source of medical costs and disability, impacting over 31 million Americans at any given time and resulting in US$100-US$200 billion per year in total healthcare costs. LBP is one of the leading causes of ambulatory care visits to US physicians; problematically, these visits often result in treatments such as opioids, surgery or advanced imaging that can lead to more harm than benefit. The American College of Physicians (ACP) Guideline for Low Back Pain recommends patients receive non-pharmacological interventions as a first-line treatment. Roadmaps exist for multidisciplinary collaborative care that include well-trained primary contact clinicians with specific expertise in the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions, such as physical therapists and doctors of chiropractic, as first-line providers for LBP. These clinicians, sometimes referred to as primary spine practitioners (PSPs) routinely employ many of the non-pharmacological approaches recommended by the ACP guideline, including spinal manipulation and exercise. Important foundational work has demonstrated that such care is feasible and safe, and results in improved physical function, less pain, fewer opioid prescriptions and reduced utilisation of healthcare services. However, this treatment approach for LBP has yet to be widely implemented or tested in a multisite clinical trial in real-world practice.

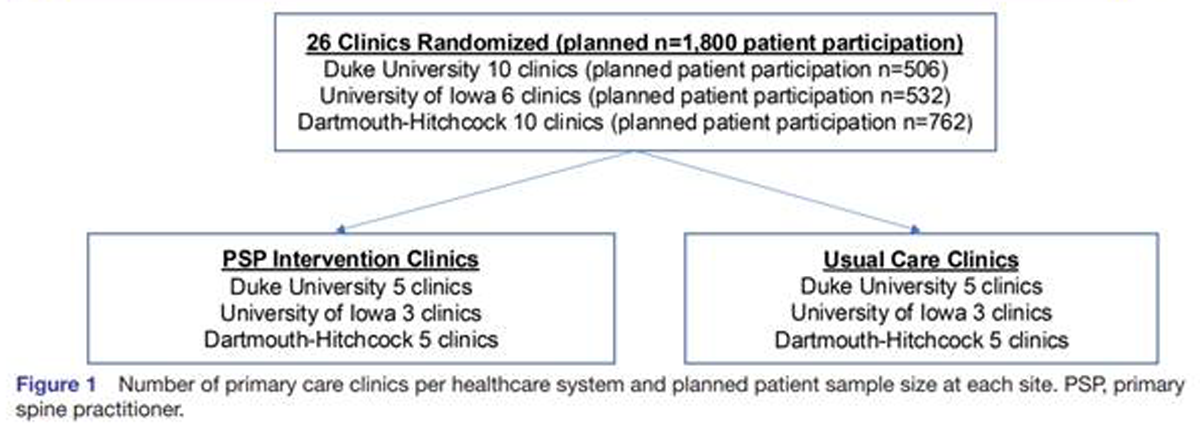

Methods and analysis: The Implementation of the American College of Physicians Guideline for Low Back Pain trial is a health system-embedded pragmatic cluster-randomised trial that will examine the effect of offering initial contact with a PSP compared with usual primary care for LBP. Twenty-six primary care clinics within three healthcare systems were randomised 1:1 to PSP intervention or usual primary care.

Primary outcomes are pain interference and physical function using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Short Forms collected via patient self-report among a planned sample of 1800 participants at baseline, 1, 3 (primary end point), 6 and 12 months. A subset of participants enrolled early in the trial will also receive a 24-month assessment. An economic analysis and analysis of healthcare utilisation will be conducted as well as an evaluation of the patient, provider and policy-level barriers and facilitators to implementing the PSP model using a mixed-methods process evaluation approach.

Ethics and dissemination: The study received ethics approval from Advarra, Duke University, Dartmouth Health and the University of Iowa Institutional Review Boards. Study data will be made available on completion, in compliance with National Institutes of Health data sharing policies.

There are more articles like this @

Methods and analysis: The Implementation of the American College of Physicians Guideline for Low Back Pain trial is a health system-embedded pragmatic cluster-randomised trial that will examine the effect of offering initial contact with a PSP compared with usual primary care for LBP. Twenty-six primary care clinics within three healthcare systems were randomised 1:1 to PSP intervention or usual primary care.

Primary outcomes are pain interference and physical function using the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Short Forms collected via patient self-report among a planned sample of 1800 participants at baseline, 1, 3 (primary end point), 6 and 12 months. A subset of participants enrolled early in the trial will also receive a 24-month assessment. An economic analysis and analysis of healthcare utilisation will be conducted as well as an evaluation of the patient, provider and policy-level barriers and facilitators to implementing the PSP model using a mixed-methods process evaluation approach.

Ethics and dissemination: The study received ethics approval from Advarra, Duke University, Dartmouth Health and the University of Iowa Institutional Review Boards. Study data will be made available on completion, in compliance with National Institutes of Health data sharing policies.

Trial registration number: ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT05626049.

Keywords: back pain; pragmatic clinical trial; primary health care.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is the leading musculoskeletal pain condition and a key source of medical costs and disability worldwide. [1–6] Up to 39% of US adults have LBP in the past 3 months, with 50%–80% reporting a significant episode in their lifetime. [7, 8] LBP impacts over 619 million people globally, [9] has increased threefold in prevalence in a 10-year period [5] and results in up to US$200 billion per year in total healthcare costs. [10, 11] Given the significance, it is no surprise that LBP is one of the leading causes of ambulatory care visits to US physicians. [12]

In 2018, 62% of US adults who reported seeing a healthcare provider for spine pain within the past year said they had seen a medical doctor. [13] Over half of LBP visits are made to primary care physicians (PCPs). [14] Unfortunately, it is becoming increasingly clear that the usual medical care for LBP, which commonly includes prescribed medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids, as well as invasive therapies like spinal fusions and epidural injections, is often ineffective or of questionable benefit. [15–17]

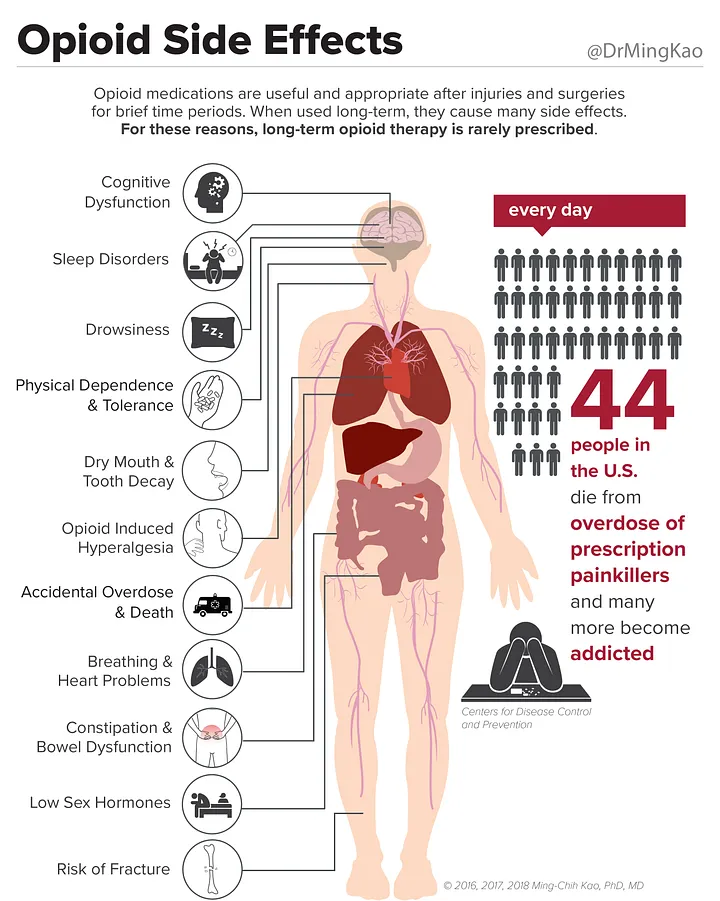

Furthermore, many of these standard treatments impose the risk of significant harm to patients. [18–24] Over 60% of opioid-related deaths are linked to chronic pain, and consistent opioid use is found in a majority (61%) of those with chronic LBP. [25] In 2012, a prescription for opioids was received by 20% of patients who visited a medical doctor for acute or chronic pain, [26] a number that is still unacceptably high. [27] Almost half of all opioid prescriptions are written by PCPs. [28]

In 2017, the American College of Physicians (ACP) guideline for LBP recommended patients receive non-pharmacological interventions as a first-line treatment. [29] To assist in the implementation of the guideline, roadmaps have been created for multidisciplinary collaborative care that place primary spine providers (PSPs) at the forefront of patient care for those with spine-related disorders, including LBP. [30–33]

The PSP model emphasises the use of doctors of chiropractic (DCs) and physical therapists (PTs) as first-line providers for LBP. These clinicians have specific expertise in treating musculoskeletal conditions and routinely employ many of the non-pharmacological approaches recommended by the ACP guideline, including spinal manipulation and exercise. Mounting evidence indicates that early treatment by DCs or PTs improves pain and functional outcomes in referral and direct-access settings. [34, 35] Important foundational work has demonstrated that PSP model care is feasible, safeand results in improved physical function, less pain, fewer opioid prescriptions and reduced utilisation of healthcare services. [34, 36, 37]

DCs and PTs are licensed as direct-access clinicians in all 50 states. [38, 39] Serious adverse events from these non-pharmacological treatments are rare, [40–42] with typically minimal side effects, such as mild muscle stiffness or soreness, commonly reported. [43–50] Such care is considerably safer than taking NSAIDs over time. [51]

DCs and PTs are well trained to perform a history and evidence-based examination to arrive at a diagnosis and then manage a patient’s care or make an appropriate referral for co-management or specialty care. Evidence supports that both DCs and PTs effectively screen and differentially diagnose musculoskeletal disorders from other systemic conditions like cancer. [52, 53] However, these studies are largely based on the use of large administrative or electronic health record (EHR) data or are observational designs. There is a need to test such models in real-world settings using rigorous randomised clinical trial designs.

The Implementation of the American College of Physicians Guideline for Low Back Pain (IMPACt-LBP) trial addresses gaps in prior studies of LBP care by implementing the PSP model of care for LBP in three health systems. The overall goal of this study is to compare usual primary care with the PSP model, which includes co-management between a DC or PT and a PCP. Patients seeking an LBP appointment at a clinic that has been randomised to PSP model care are asked if they would consider seeing a DC or PT first.

The primary objective is to determine if patients with LBP in intervention will have improved outcomes when compared with usual care based on the change in Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Pain Interference and Physical Function [54] scores from baseline to 3 months.

The secondary objective is to compare the effects of PSP model care with usual care for LBP at 3, 6 and 12 months on the Pain Catastrophising Scale-4 item short form, PROMIS Global-10 (V.1.2), opioid use and LBP-associated procedures and treatments including: imaging and diagnostic testing, provider visits, surgical procedures, medication prescriptions, hospital admissions and emergency room visits.

Our hypotheses are that patients with LBP asked to initiate contact with PSP clinicians will experience improved physical function, decreased pain, decreased opioid and other LBP-related medication prescriptions, improved patient satisfaction and decreased costs and utilisation of healthcare services when compared with patients with LBP who are not asked to initiate contact with a PSP first.

Leave A Comment