Guideline for Opioid Therapy and Chronic Noncancer Pain

SOURCE: CMAJ 2017 (May 8); 189 (18): E659–E666

Jason W. Busse, DC PhD, Samantha Craigie, MSc, David N. Juurlink, MD PhD, D. Norman Buckley, MD, Li Wang, PhD, Rachel J. Couban, MA MISt, Thomas Agoritsas, MD PhD, Elie A. Akl, MD PhD, Alonso Carrasco-Labra, DDS MSc, Lynn Cooper, BES, Chris Cull, Bruno R. da Costa, PT PhD, Joseph W. Frank, MD MPH, Gus Grant, AB LLB MD, Alfonso Iorio, MD PhD, Navindra Persaud, MD MSc, Sol Stern, MD, Peter Tugwell, MD MSc, Per Olav Vandvik, MD PhD, Gordon H. Guyatt, MD MSc

Jason W. Busse

Department of Anaesthesia

McMaster University

| New Canadian Opioid Guidelines Recommends Chiropractic As Care OptionFROM: World Federation of Chiropractic Monday, May 8, 2017A new Canadian guideline published today (May 8, 2017) in the Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ) strongly recommends doctors to consider non-pharmacologic therapy, including chiropractic, in preference to opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain.The guideline is the product of an extensive review of evidence involving stakeholders from medical, non-medical, regulatory, and patient stakeholders.The lead author, Dr Jason Busse DC, PhD is a graduate of Canadian Memorial Chiropractic College and is an Associate Professor in the Department of Anaesthesia at McMaster University. Other authors of the guideline include those from the fields of physiotherapy, dentistry, public health and medicine. Chronic non-cancer pain (CNCP) is defined as pain lasting more than 3 months that is not associated with malignancy. It is estimated that up to 20% of adult Canadians suffer with CNCP and, the guideline says, is the leading cause of health resource utilization and disability among working age adults. Behind the USA, Canada has the second-highest level of opioid prescribing in the world. It is an enormous issue, with a doubling of admissions to publicly-funded opioid-related treatment programs between 2004 and 2012. In 2015, over 2000 Canadians died of opioid overdose, with final figures expected to be higher in 2016. Many of these deaths were associated with Fentanyl, the same opioid cited as being the cause of death of the musician Prince in 2016. Other commonly used opioid drugs are Percocet, OxyContin, Dilaudid and morphine.

The new guidelines significantly revise those published in 2010 with a clear message that opioids should not be the first-line therapy in CNCP and should only be used as a last, carefully dose-controlled resort after all other options have been exhausted. Another key recommendation is that MDs do not simply keep raising the dose level of opioids if recommended levels are not providing effective relief, and to avoid opioids altogether where there is a history of substance abuse or mental health issues. None of this is relevant to those already addicted to opioids. The guideline addresses this issue by advocating a tapering down of doses over time, utilizing multidisciplinary care options, such as chiropractic. A keynote speaker at the joint WFC/ACC/ACA Conference, DC2017, Dr Brian Goldman, has spoken out strongly against MDs prescribing opioids, but says that the guideline must be supported by national programs to encourage compliance with the guideline’s recommendations. With many users of opioids doing so due to chronic back pain or other musculoskeletal disorders, the recommendation to primary care physicians to optimize their use of non-opioid medications and non-pharmacological therapy has the potential to increase utilization of chiropractic. Secretary-General of the World Federation of Chiropractic, Richard Brown, commented:

The WFC Public Health Committee has identified opioid overuse as one of its key priority areas. Its Chair, Dr Chris Cassirer D.Sc, MPH is clear on how chiropractors can make a difference. He remarked:

Later this month, the WFC will be in Geneva at the World Health Assembly and will meet with representatives of the World Health Organization to discuss how chiropractic is contributing to global public health initiatives. As the only chiropractic non-governmental organization in official relations with WHO, the WFC is committed to supporting key strategies in a range of health areas, including the provision of non-pharmacologic health care around the world. |

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

Chronic noncancer pain includes any painful condition that persists for at least three months and is not associated with malignant disease. [1] According to seven national surveys conducted between 1994 and 2008, 15%–19% of Canadian adults live with chronic noncancer pain. [2] Chronic noncancer pain interferes with activities of daily living, has a major negative impact on quality of life and physical function, [3] and is the leading cause of health resource utilization and disability among working-age adults. [4, 5]

In North America, clinicians commonly prescribe opioids for acute pain, palliative care (in particular, for patients with cancer) and chronic noncancer pain. Canada has the second highest rate per capita of opioid prescribing in the world when measured using defined daily doses, and the highest when defined using morphine equivalents dispensed, with more than 800 morphine equivalents per capita in 2011. [6, 7]

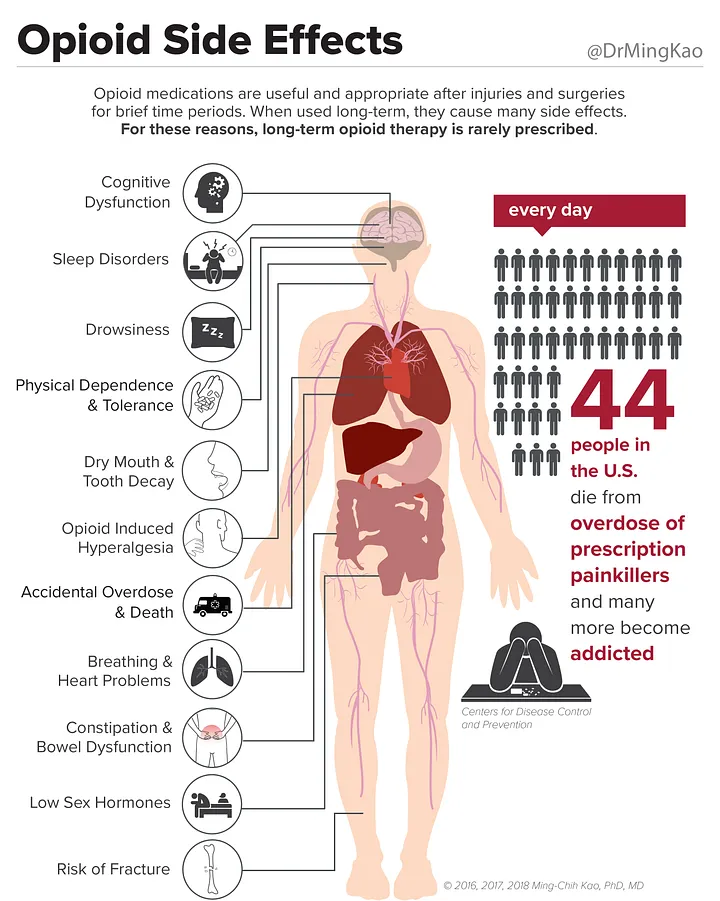

Substantial risks accompany the use of opioids in chronic noncancer pain. In Ontario, admissions to publicly funded treatment programs for opioid-related problems doubled from 2004 to 2013, from 8,799 to 18,232. [8, 9] Among Ontarians receiving social assistance, 1 of every 550 patients started on chronic opioid therapy died of opioid-related causes at a median of 2.6 years from the first opioid prescription, while 1 in 32 of those receiving 200 mg morphine equivalents daily (MED) or more died of opioid-related causes. [10] An estimated 2000 Canadians died from opioid-related poisonings in 2015 [11] and initial numbers for 2016 are higher, with most deaths attributed to fentanyl. [12]

In 2010, the National Opioid Use Guideline Group offered recommendations for safe and effective use of opioids. [13] Many of the recommendations were nonspecific and almost all supported the prescribing of opioids; the guideline provided few suggestions about when not to prescribe. [11] A time-series analysis in Ontario, Canada, from 2003 to 2014, found a slight decline in overall opioid prescribing, but no change in rates of fatal opioid overdose and increases in both high-dose opioid prescribing and opioid-related hospital visits. Moreover, 40% of recipients of long-acting opioids received > 200 mg MED, and 20% received > 400 mg MED. [14]

This updated guideline incorporates all new evidence published subsequent to the literature search that was used to inform the 2010 guideline. It adheres to standards for trustworthy guidelines [15] and aspires to promote evidence-based prescribing of opioids for chronic noncancer pain. The full guideline is available in Appendix 1.

Scope

Read the rest of this Full Text article now!

Leave A Comment