Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians

SOURCE: Annals of Internal Medicine 2017 (Apr 4); 166 (7): 514–530 ~ FULL TEXT

Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MHA; Timothy J. Wilt, MD, MPH;

Robert M. McLean, MD; Mary Ann Forciea, MD;

for the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians (*)

From the American College of Physicians

and Penn Health System,

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania;

Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center,

Minneapolis, Minnesota; and

Yale School of Medicine,

New Haven, Connecticut.

|

The American College of Physicians (ACP) released updated guidelines this week that recommend the use of noninvasive, non-drug treatments for low back pain before resorting to drug therapies, which were found to have limited benefits. One of the non-drug options cited by ACP is spinal manipulation. Chiropractors, who diagnose and treat musculoskeletal disorders, are experts in spinal manipulation.

On May 1, 2017, the New York Times published an editorial by Aaron E. Carroll, M.D., that mentions the new guideline in a generally positive light. The article appeared in a major, mainstream publication read by millions of people. “Spinal manipulation — along with other less traditional therapies like heat, meditation and acupuncture — seems to be as effective as many other more medical therapies we prescribe, and as safe, if not safer,” he wrote. Talking points on new ACP guideline:

|

DESCRIPTION: The American College of Physicians (ACP) developed this guideline to present the evidence and provide clinical recommendations on noninvasive treatment of low back pain.

METHODS: Using the ACP grading system, the committee based these recommendations on a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials and systematic reviews published through April 2015 on noninvasive pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments for low back pain. Updated searches were performed through November 2016. Clinical outcomes evaluated included reduction or elimination of low back pain, improvement in back-specific and overall function, improvement in health-related quality of life, reduction in work disability and return to work, global improvement, number of back pain episodes or time between episodes, patient satisfaction, and adverse effects.

TARGET AUDIENCE AND PATIENT POPULATION: The target audience for this guideline includes all clinicians, and the target patient population includes adults with acute, subacute, or chronic low back pain.

RECOMMENDATION 1: Given that most patients with acute or subacute low back pain improve over time regardless of treatment, clinicians and patients should select nonpharmacologic treatment with superficial heat (moderate-quality evidence), massage, acupuncture, or spinal manipulation (low-quality evidence). If pharmacologic treatment is desired, clinicians and patients should select nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or skeletal muscle relaxants (moderate-quality evidence). (Grade: strong recommendation).

| WARNING: Before following Recommendation #1, please review the Contra-indications to NSAIDS use. |

There are more articles like this @ our:

RECOMMENDATION 2: For patients with chronic low back pain, clinicians and patients should initially select nonpharmacologic treatment with exercise, multidisciplinary rehabilitation, acupuncture, mindfulness-based stress reduction (moderate-quality evidence), tai chi, yoga, motor control exercise, progressive relaxation, electromyography biofeedback, low-level laser therapy, operant therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, or spinal manipulation (low-quality evidence). (Grade: strong recommendation).

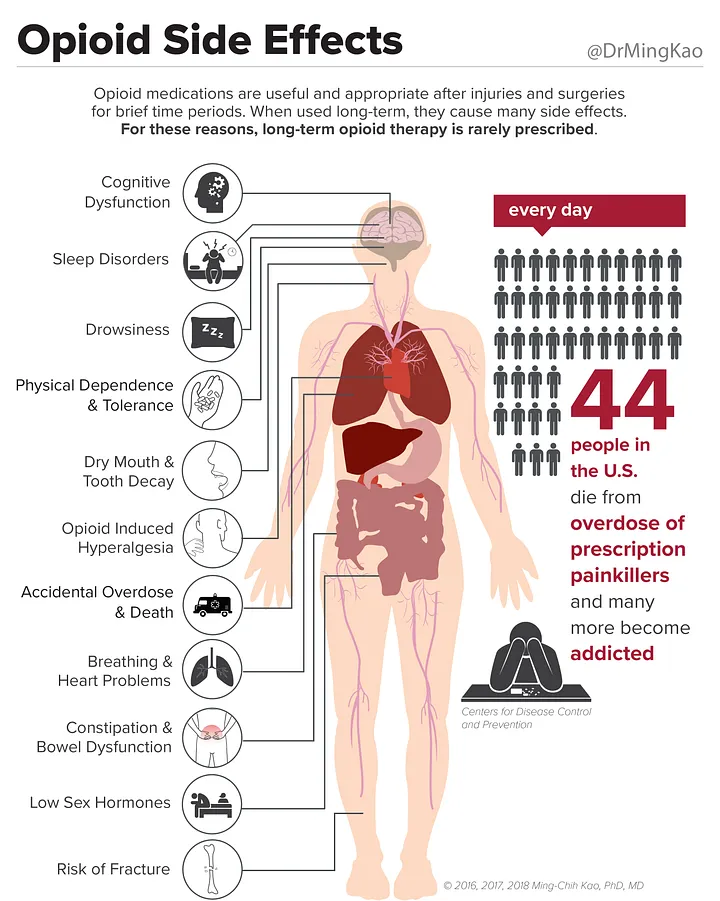

RECOMMENDATION 3: In patients with chronic low back pain who have had an inadequate response to nonpharmacologic therapy, clinicians and patients should consider pharmacologic treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as first-line therapy, or tramadol or duloxetine as second-line therapy. Clinicians should only consider opioids as an option in patients who have failed the aforementioned treatments and only if the potential benefits outweigh the risks for individual patients and after a discussion of known risks and realistic benefits with patients. (Grade: weak recommendation, moderate-quality evidence).

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Background

Low back pain is one of the most common reasons for physician visits in the United States. Most Americans have experienced low back pain, and approximately one quarter of U.S. adults reported having low back pain lasting at least 1 day in the past 3 months [1]. Low back pain is associated with high costs, including those related to health care and indirect costs from missed work or reduced productivity [2]. The total costs attributable to low back pain in the United States were estimated at $100 billion in 2006, two thirds of which were indirect costs of lost wages and productivity [3].

Low back pain is frequently classified and treated on the basis of symptom duration, potential cause, presence or absence of radicular symptoms, and corresponding anatomical or radiographic abnormalities. Acute back pain is defined as lasting less than 4 weeks, subacute back pain lasts 4 to 12 weeks, and chronic back pain lasts more than 12 weeks. Radicular low back pain results in lower extremity pain, paresthesia, and/or weakness and is a result of nerve root impingement. Most patients with acute back pain have self-limited episodes that resolve on their own; many do not seek medical care [4]. For patients who do seek medical care, pain, disability, and return to work typically improve rapidly in the first month [5]. However, up to one third of patients report persistent back pain of at least moderate intensity 1 year after an acute episode, and 1 in 5 report substantial limitations in activity [6]. Many noninvasive treatment options are available for radicular and nonradicular low back pain, including pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions.

SOURCE: Read the rest of this Full Text article now!

Leave A Comment