An Updated Overview of Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Non-specific Low Back Pain in Primary Care

SOURCE: Eur Spine J. 2010 (Dec); 19 (12): 2075–2094

Koes BW, van Tulder M, Lin CW, Macedo LG, McAuley J, Maher C.

Department of General Practice,

Erasmus MC, P.O. Box 2040, 3000 CA,

Rotterdam, The Netherlands

| This review of national and international guidelines conducted by Koes et. al. points out the disparities between guidelines with respect to spinal manipulation and the use of drugs for both chronic and acute low back pain. Another review of guidelines published in June 2010 also noted a great degree of similarity between guidelines and that: |

The Abstract

The aim of this study was to present and compare the content of (inter)national clinical guidelines for the management of low back pain. To rationalise the management of low back pain, evidence-based clinical guidelines have been issued in many countries. Given that the available scientific evidence is the same, irrespective of the country, one would expect these guidelines to include more or less similar recommendations regarding diagnosis and treatment. We updated a previous review that included clinical guidelines published up to and including the year 2000.

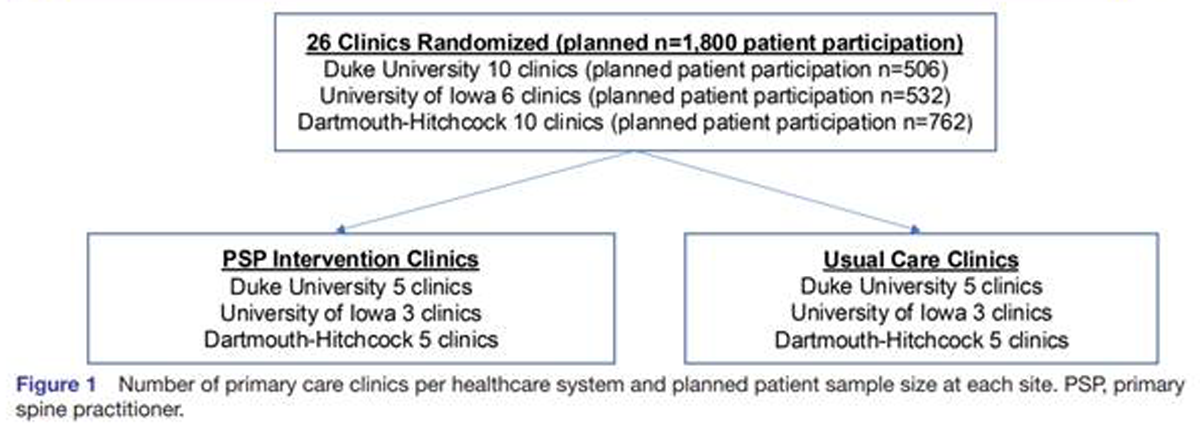

Guidelines were included that met the following criteria: the target group consisted mainly of primary health care professionals, and the guideline was published in English, German, Finnish, Spanish, Norwegian, or Dutch. Only one guideline per country was included: the one most recently published. This updated review includes national clinical guidelines from 13 countries and 2 international clinical guidelines from Europe published from 2000 until 2008. The content of the guidelines appeared to be quite similar regarding the diagnostic classification (diagnostic triage) and the use of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. Consistent features for acute low back pain were the early and gradual activation of patients, the discouragement of prescribed bed rest and the recognition of psychosocial factors as risk factors for chronicity.

There are more articles like this @ our:

and the:

For chronic low back pain, consistent features included supervised exercises, cognitive behavioural therapy and multidisciplinary treatment. However, there are some discrepancies for recommendations regarding spinal manipulation and drug treatment for acute and chronic low back pain. The comparison of international clinical guidelines for the management of low back pain showed that diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations are generally similar. There are also some differences which may be due to a lack of strong evidence regarding these topics or due to differences in local health care systems. The implementation of these clinical guidelines remains a challenge for clinical practice and research.

Keywords: Low back pain, Clinical guidelines, Review, Diagnosis, Treatment

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

Low back pain remains a condition with a relatively high incidence and prevalence. Following a new episode, the pain typically improves substantially but does not resolve completely during the first 4–6 weeks. In most people the pain and associated disability persist for months; however, only a small proportion remains severely disabled [1]. For those whose pain does resolve completely, recurrence during the next 12 months is not uncommon [2, 3].

There is a wide acceptance that the management of low back pain should begin in primary care. The challenge for primary care clinicians is that back pain is but one of many conditions that they manage. For example while back pain, in absolute numbers, is the eighth most common condition managed by Australian GPs, it only accounts for 1.8% of their case load [4]. To assist primary care practitioners to provide care that is aligned with the best evidence, clinical practice guidelines have been produced in many countries around the world.

The first low back pain guideline was published in 1987 by the Quebec Task Force with authors pointing to the absence of high-quality evidence to guide decision making [5]. Since that time there has been a strong growth in research addressing diagnosis and prognosis but especially research on therapy. As an example of this growth, at the time of the Spitzer guideline [5] there were only 108 randomised controlled trials evaluating physiotherapy treatments for low back pain but as at April 2009 there were 958.1 The Cochrane database (Central) currently lists more than 2500 controlled trials evaluating treatment for back and neck pain. The evidence from these trials for most interventions is summarised in systematic reviews and meta-analysis. The Cochrane Back Review Group, for example, has now published 32 systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials evaluating interventions for low back pain. In the near future, systematic reviews of studies evaluating diagnostic intervention for low back pain will also be included in the Cochrane Library.

Read the rest of this Full Text article now!

Leave A Comment