Physical Examination of the Neck and Cervical Spine

We would all like to thank Dr. Richard C. Schafer, DC, PhD, FICC for his lifetime commitment to the profession. In the future we will continue to add materials from RC’s copyrighted books for your use.

This is Chapter 8 from RC’s best-selling book:

“Spinal and Physical Diagnosis”

These materials are provided as a service to our profession. There is no charge for individuals to copy and file these materials. However, they cannot be sold or used in any group or commercial venture without written permission from ACAPress.

Chapter 8: Physical Examination of the Neck and Cervical Spine

In general, the neck viscerally serves as a channel for vital vessels and nerves, the trachea, esophagus, spinal cord, and as a site for lymph and endocrine glands. From a musculoskeletal viewpoint, the neck provides stability and support for the cranium, and a flexible and protective spine for movement, balance adaptation, and housing of the spinal cord and vertebral artery. Cervical flexion, extension, and rotation contribute to one’s scope of vision.

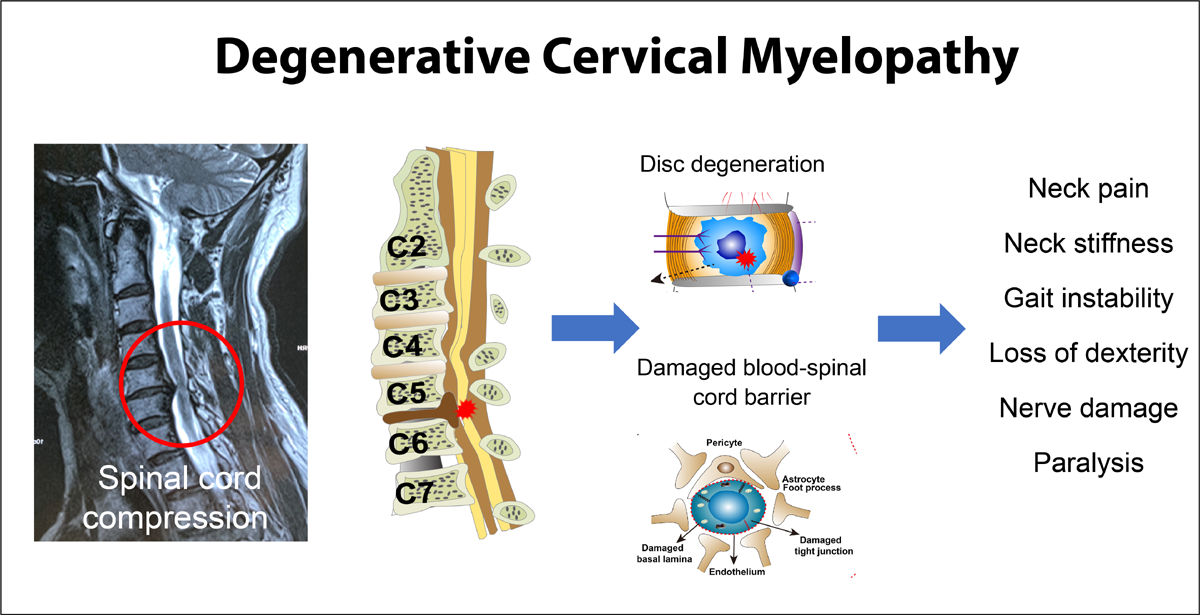

From a biomechanical viewpoint, primary cervical dysarthrias may reflect themselves in the total habitus; from a neurologic viewpont, insults many manifest themselves throughout the motor, sensory, and autonomic nervous systems. Many peripheral nerve symptoms in the shoulder, arm, and hand will find their origin in the brachial plexus and cervical spine. Nowhere in the spine is the relationship between the osseous structures and the surrounding neurologic and vascular beds as intimate or subject to disturbance as it is in the neck.

Neck pain must be differentiated as to its date of onset and chronology, site and distribution, type (intermittent, constant), duration (acute, chronic), character (sharp, dull, lanciating), relation to posture (rest, occupation, recreation), and associated problems. Nonpharyngeal pain on swallowing may be traced to an anterior cervical spinal pathology such as bony protuberance or osteophytes, infection, mass or tumor. Pain is often referred to the neck from the TMJ, mandibular or dental infection, or sinus infection.

Inspection of the Neck

As with all gross and regional inspection, the observation process begins when the examiner first is introduced to the patient and continues through the history and examination process. Abnormalities in the neck may be of local etiology (eg, infection, neoplasm, trauma) or be a manifestation of a general disorder (eg, curvature, spondylosis, leukemia, systemia).

With the patient in the sitting position, inspect first for gross abnormalities and then details. Some examiners prefer to inspect and palpate the anterior neck in the supine position and palpate the posterior aspect in the supine position.

Check for scars (eg, surgical, tubercular adenitis, trauma), blisters, discolorations, skin texture and lesions, and pulsatile movements. Observe congenital defects such as pteryigium colli (webbed neck) or congenital torticollis.

Note any parotid or submaxillary gland enlargement (eg, infection, duct stone, tumor) if this has not been done previously. Check for fixed or movable masses, and transilluminate if present. Thyroglossal cysts, usually in the midline, often move headward when the tongue is protruded.

Have the patient swallow, and note the function of the cricoid cartilage area and possible superior movement of the thyroid gland. Check the trachea for midline alignment. If the thyroid is visible, note its size, shape, symmetry, and presence of nodules.

Inspect for abnormal shadows, neck contours, curvatures, and restricted movements. Note relationship of neck, head, and shoulders from an A-P, lateral, and rotational standpoint. Check head tilt, sway, carriage during rest and gait, and other abnormal postural expressions.

Keep in mind that tumors of the cervical spine are usually secondary and that chronic degenerative disc disease and congenital anomalies may be asymptomatic for many years. Unlike the lumbar region, cervical disc herniations are not frequently associated with severe trauma; however, nerve root or cord compression has a high incidence.

Venous thrombosis, mediastinal tumors, and inflammatory exudates may produce visible and palpable edema in the neck.

Bony and Soft Tissue Palpation

| Review the complete Chapter (including sketches and Tables) at the ACAPress website |

Many errors such as missing spaces, “nuchial”, “lieing” distract from the content of the article.

Thanks Shelly

I spend up to 3 hours transferring each of RCs articles from their old formatting into the WordPress templates for publication.

Unfortunately, the spacing issues from these old Word 2.0 documents transfers invisably to the WordPress template, and they are not always easy to spot in the small box provided on WordPress.

The material is still extremely valuable, but there’s just so much time I can spend on any given chapter. The only other option for our readers would be for them to check these out at a Chiropractic Library, since they are out-of-print. And that’s usually not an option for most of our readers.

I corrected the 2 mis-spellings you noted. Thanks again for your posting!

This is great material for the examination of the cervical spine.

Thanks Dr. Frank and Dr. Richard. I love all the info, especially the subluxation stuff!

Marco, D.C.

Very informative article… Looking forward for more articles on your blog

HI

This article is very helpful, and things you said is very knowledgeable and helpful for the viewers. We are working in the same area, helping people get relief from neck and back pain.

Thanks

Chris