Is There a Difference in Head Posture and Cervical Spine Movement in Children With and Without Pediatric Headache?

SOURCE: Eur J Pediatr. 2013 (Oct); 172 (10): 1349–1356

Kim Budelmann, Harry von Piekartz, Toby Hall

University of Applied Science,

Osnabrück, Germany

Pediatric headache is an increasingly reported phenomenon. Cervicogenic headache (CGH) is a subgroup of headache, but there is limited information about cervical spine physical examination signs in children with CGH. Therefore, a cross-sectional study was designed to investigate cervical spine physical examination signs including active range of motion (ROM), posture determined by the craniovertebral angle (CVA), and upper cervical ROM determined by the flexion-rotation test (FRT) in children aged between 6 and 12 years. An additional purpose was to determine the degree of pain provoked by the FRT.

Thirty children (mean age 120.70 months [SD 15.14]) with features of CGH and 34 (mean age 125.38 months [13.14]) age-matched asymptomatic controls participated in the study. When compared to asymptomatic controls, symptomatic children had a significantly smaller CVA (p < 0.001), significantly less active ROM in all cardinal planes (p < 0.001), and significantly less ROM during the FRT (p < 0.001), especially towards the dominant headache side (p < 0.001).

In addition, symptomatic subjects reported more pain during the FRT (p < 0.001) and there was a significant negative correlation (r = -0.758, p < 0.001) between the range recorded during the FRT towards the dominant headache side and FRT pain intensity score. This study found evidence of impaired function of the upper cervical spine in children with CGH and provides evidence of the clinical utility of the FRT when examining children with CGH.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

Introduction

There are more articles like this @ our:

Chiropractic Pediatrics Section

and our:

Headache and Chiropractic Page

and our:

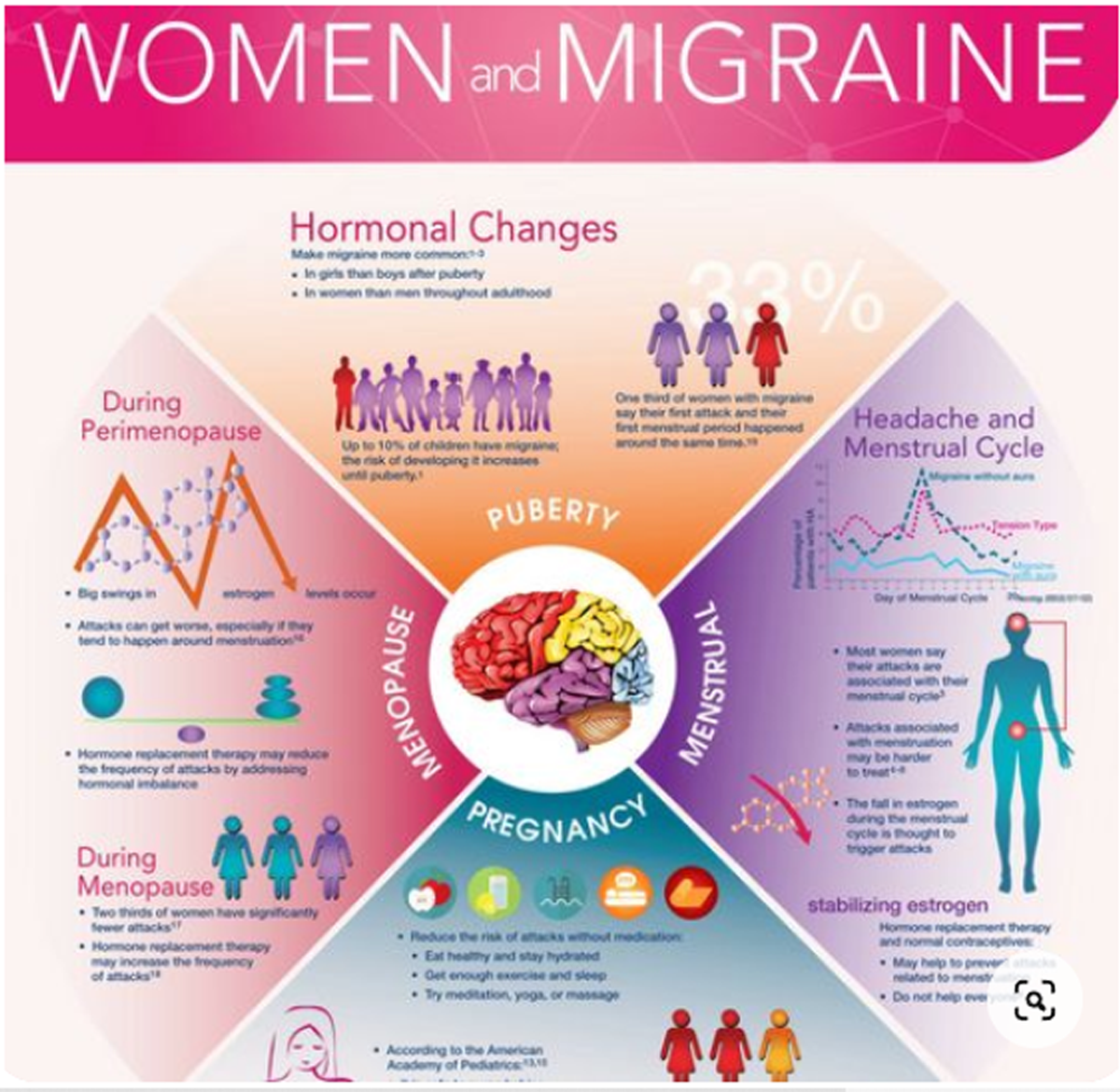

Headache is the most frequently reported pain in children [28], with an even sex distribution up to the age of 12 [2, 25, 28], after which more females than males suffer. [25, 49] Pediatric headache prevalence rates are 50% during school years, increasing during adolescence to 80%. [41] Studies have shown that children with more severe headache report lower quality in life, in general [5], while early onset headache can be predictive of ongoing problems during adolescence and adult life [8, 18], indicating the importance of diagnosis and management.

Cognitive, behavioral, and emotional factors have been shown to play important roles in generating headache in children. [4, 33] In addition, physical factors, such as schoolwork, increased forward head posture, and prolonged static postures of the head [11, 34, 49], have also been shown to play a role in triggering headache. Hence, headache diagnosis is important, particularly for physiotherapists who have to consider whether physical treatment may be helpful to alleviate symptoms.

There are numerous structures and disorders capable of causing headache. [22] The International Headache Society [20] has formulated the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) to enable differentiation of primary and secondary headache disorders. One form of secondary headache is cervicogenic headache (CGH), where pain is believed to originate from a disorder in the neck. [20] The anatomical basis for pain perceived in the head is due to the convergence of afferent impulses from the upper three cervical nerve roots with the trigeminal nerve in the trigeminocervical nucleus. [7, 22] The ICHD [20] is commonly used to diagnose headache in adults and relies mainly on subjective descriptors from the patient. [40] In pediatric headache, such subjective differentiation is more difficult [27, 49] and physical signs become increasingly important to identify CGH.

Read the rest of this Full Text article now!

Leave A Comment