Sophisticated Research Design in Chiropractic and Manipulative Therapy;

“What You Learn Depends on How You Ask.”

Part C: Mixed Methods: “Why Can’t Science And Chiropractic Just Be Friends?”

SOURCE: Chiropractic Journal of Australia 2016; 44 (2): 1–21

Lyndon G. Amorin-Woods, BAppSci(Chiropractic), MPH

Senior Clinical Supervisor;

Murdoch University Chiropractic Clinic

School of Health Professions,

Discipline of Chiropractic

Murdoch University South Street campus,

90 South Street, Murdoch,

Western Australia 6150

| Enjoy Part 1: Quantitative Research: Size Does Matter Enjoy Part 2: Qualitative Research: Quality vs. Quantity |

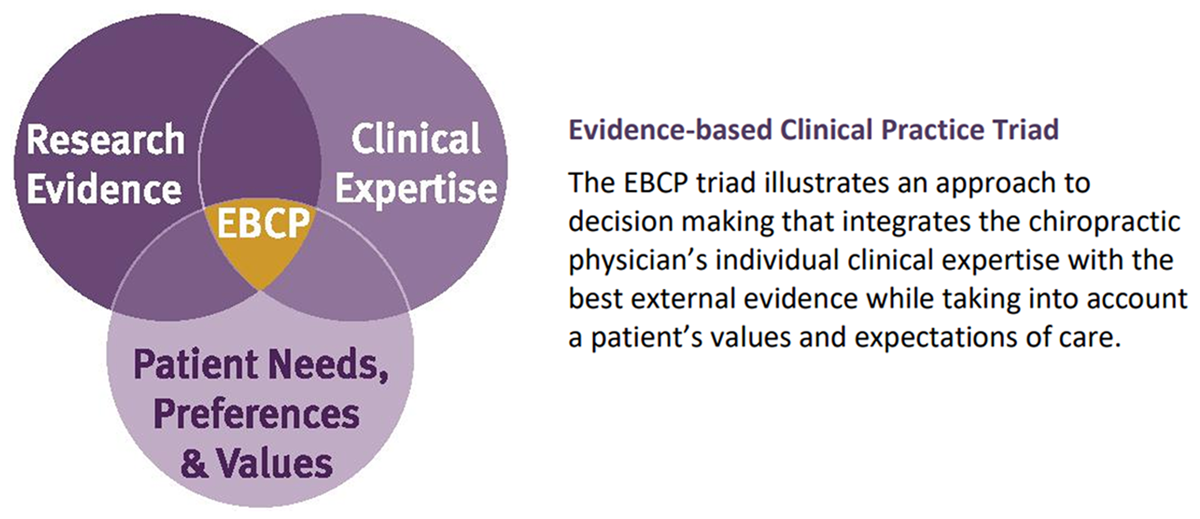

Many commentators have recognised the limitations and inapplicability of the traditional quantitative pyramid hierarchy especially with respect to complementary and alternative (CAM) health care, observing the way Evidence-based Practice [EBP] is sometimes implemented is controversial, not only within the chiropractic profession, but in all other healthcare disciplines, including medicine itself. A phased approach to the development and evaluation of complex interventions can help researchers define the research process and complex interventions may require use of both qualitative and quantitative methods. The chiropractic profession has little to fear from evidence-based practice; in fact it should be used productively to improve patient care, clinical outcomes and the standing of the profession in the eyes of the public, other health professions and legislators.

Keywords Evidence-Based Practice; Mixed Methods; Research Design

INTRODUCTION

Many scientists have recognised the limitations and inapplicability of the traditional quantitative pyramid hierarchy especially with respect to complementary and alternative (CAM) health care, including chiropractic. Over the last decade some authors have suggested refinements of the model, for instance; in the place of an evidence hierarchy, Jonas [1] suggested the construction of an “evidence house” with “rooms” for different types of information and purposes and later presented a refined circular model. [1]

Jonas [1] observed:

“… the best evidence may be observational data from clinical practice that can estimate the likelihood of a patient’s recovery in a realistic context. [2] Patient’s illnesses are complex physical, psychological, and social experiences that cannot be reduced to single, objective measures. [3] Personal experience of illness might sometimes be captured only through qualitative research. [4] The “best” evidence thus may be the meaning that patients give to their illness and recovery. At other times, the “best” evidence may come from laboratory studies. [5] Arranging types of evidence in a “hierarchy” obscures the fact that sometimes the best evidence is not objective, not additive, and sometimes not even clinical”. [6]

This ‘house’ model evolved to be depicted by Walach et al as being circular instead of hierarchical. [7] This model was derived from the experience and history of evaluation methodology in the social sciences. [8, 9] Again, rather than postulating a single “best method” this view acknowledges that there are optimal methods for answering specific questions, and that a composite of all methods constitutes best scientific evidence. Sometimes there may exist nothing but expert opinion on a clinical question; thus, it becomes ‘best evidence.’ However when making decisions with respect to patient care, it is imperative to use the highest-level evidence available. When evidence is lacking, clinical decisions may still be made on biological plausibility, cost-effectiveness, feasibility and avoidance of harm. [10-12]

Read the rest of this Full Text article now!

Leave A Comment