Spinal Manipulative Therapy and Somatosensory Activation

SOURCE: J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2012 (Oct); 22 (5): 785–794

Joel G Pickar, DC PhD and Philip S Bolton, DC PhD

Palmer Center for Chiropractic Research,

Palmer College of Chiropractic,

Davenport, IA, USA.

pickar_j@palmer.edu

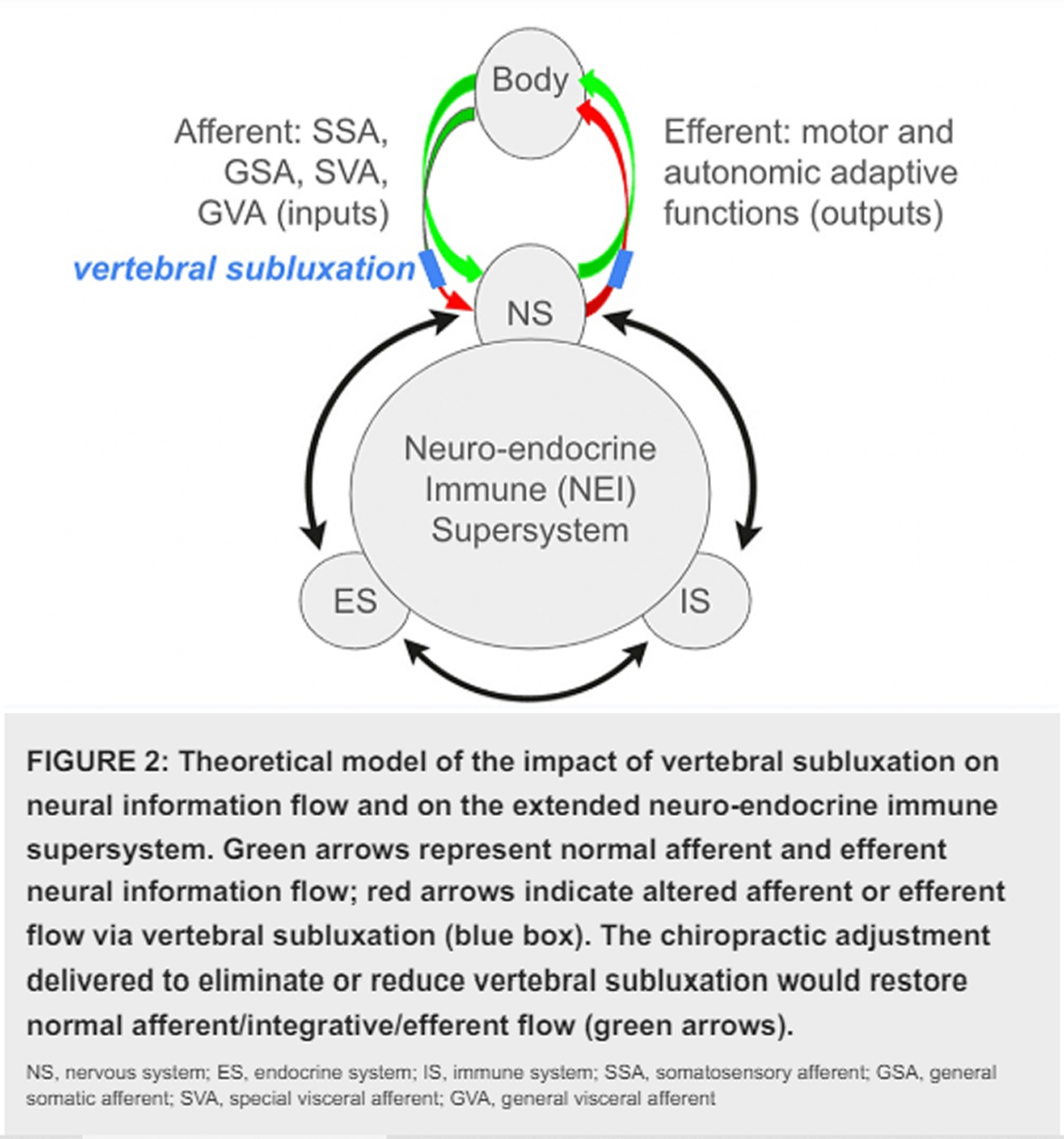

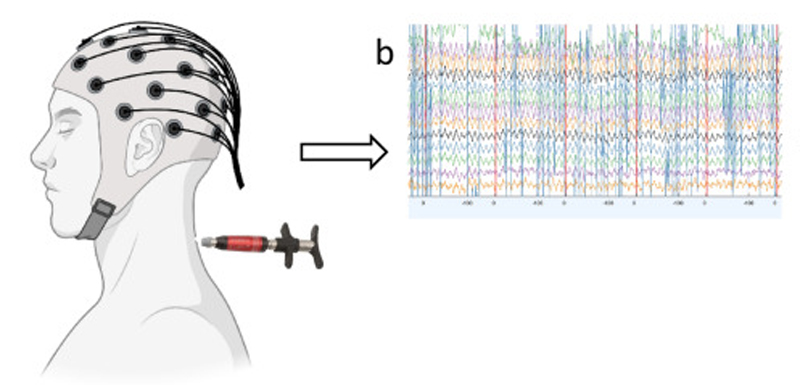

Manually-applied movement and mobilization of body parts as a healing activity has been used for centuries. A relatively high velocity, low amplitude force applied to the vertebral column with therapeutic intent, referred to as spinal manipulative therapy (SMT), is one such activity. It is most commonly used by chiropractors, but other healthcare practitioners including osteopaths and physiotherapists also perform SMT. The mechanisms responsible for the therapeutic effects of SMT remain unclear. Early theories proposed that the nervous system mediates the effects of SMT. The goal of this article is to briefly update our knowledge regarding several physical characteristics of an applied SMT, and review what is known about the signaling characteristics of sensory neurons innervating the vertebral column in response to spinal manipulation. Based upon the experimental literature, we propose that SMT may produce a sustained change in the synaptic efficacy of central neurons by evoking a high frequency, bursting discharge from several types of dynamically-sensitive, mechanosensitive paraspinal primary afferent neurons.

From the FULL TEXT Article:

INTRODUCTION

Manually-applied movement and mobilisation of body parts as a healing activity has been used for centuries (Wiese & Callender, 2005). A relatively high velocity, low amplitude force applied to the vertebral column with therapeutic intent, referred to as spinal manipulative therapy (SMT), is one such activity. It is most commonly used by chiropractors, but other healthcare practitioners including osteopaths and physiotherapists use it as well. Although SMT has been advocated for a wide range of health problems (Ernst & Gilbey, 2010), currently available best evidence suggests it has a therapeutic effect on people suffering some forms of acute neck and back pain particularly when it is used in combination with other therapies (Brønfort et al, 2004; Brønfort et al, 2010; Dagenais et al, 2010; Miller et al 2010; Walker et al 2010; Lau et al 2011). Its effect on chronic low back pain is less clear (Rubinstein et al 2011; Walker et al 2010).

There are more articles like this @ our:

SMT is typically applied when dysfunctional areas of the vertebral column are found. Clinicians identify these areas based upon palpatory changes in the texture and tone of paraspinal soft tissues, the ability to elicit pain and/or tenderness from these tissues, asymmetries in hard or soft tissue landmarks, and restrictions in spinal joint motion (Kuchers & Kappler 2002; Sportelli et al 2005). The clinician’s goal in applying a spinal manipulation is to restore normal motion and normalize physiology of the neuromusculoskeletal system in particular and potentially other physiological systems affected by the dysfunction.

The mechanisms responsible for the therapeutic effects of SMT remain unclear. Early theories proposed that the nervous system likely mediates the effects of SMT. For example, Korr (1975) proposed that SMT alters or modulates proprioceptive afferent input to the central nervous system. Twelve years later Gillette (1987) provided a speculative description of all afferent input likely to arise from SMT of the lumbar spine. The force-time profile of SMT, based upon the one study available at the time, was trapezoidal in shape, reaching a peak force of nearly 200N and lasting nearly 400ms before returning to pre-SMT levels. Identification of afferents likely activated by SMT was based upon a review of the experimental evidence describing the response characteristics of all known somatic mechanosensitive receptors to the mechanical features of the stimuli that activated them (eg, force magnitude, rate of force application). Much of the data concerning receptor-type and response characteristics were derived from studies involving the appendicular somatosensory system since little was known at the time about the axial somatosensory system. Consequently Gillette’s description (Gillette, 1987) provided a hypothetical profile of the afferent activity arising during SMT.

Since Gillette’s (1987) benchmark paper, considerably more is known about the morphology of the vertebral column’s somatosensory system (for example see Giles & Taylor 1987; Richmond et al 1988; Groen et al 1990; McLain 1994; Jiang et al 1995; Bolton 1998). Table 1 summarises receptor types that have been found in paravertebral tissues. Similarly, more is now known about the mechanical characteristics of SMT. Additionally, in vivo and cadaveric studies have better informed us about the kinematics of vertebral motion segments produced by SMT. Together these new data provide a more informed basis for modelling SMT activation of the axial somatosensory system.

Table 1.

This table lists the receptors that have been identified in paravertebral tissues of the Cervical (C), Thoracic (T), Lumbar (L), or Coccygeal (Cx) regions of the vertebral column using morphological (M) or physiological (P) studies. The species in which the respective receptors have been studies is listed together with one reference to a study involving the species and study type.

Read the rest of this Full Text article now!

Leave A Comment