Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain: A Joint Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society

SOURCE: Annals of Internal Medicine 2007 (Oct 2); 147 (7): 478–491

Roger Chou, MD; Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MHA; Vincenza Snow, MD; Donald Casey, MD, MPH, MBA; J. Thomas Cross, Jr, MD, MPH; Paul Shekelle, MD, PhD; Douglas K. Owens, MD, MS

Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee

of the American College of Physicians

and the American College of Physicians/

American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guidelines Panel*

| Review the complete Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Low Back Pain: Evidence Review (482 page Adobe Acrobat file) |

From the FULL TEXT Article:

The Abstract

Recommendation 1: Clinicians should conduct a focused history and physical examination to help place patients with low back pain into 1 of 3 broad categories: nonspecific low back pain, back pain potentially associated with radiculopathy or spinal stenosis, or back pain potentially associated with another specific spinal cause. The history should include assessment of psychosocial risk factors, which predict risk for chronic disabling back pain (strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence).

Recommendation 2: Clinicians should not routinely obtain imaging or other diagnostic tests in patients with nonspecific low back pain (strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence).

Recommendation 3: Clinicians should perform diagnostic imaging and testing for patients with low back pain when severe or progressive neurologic deficits are present or when serious underlying conditions are suspected on the basis of history and physical examination (strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence).

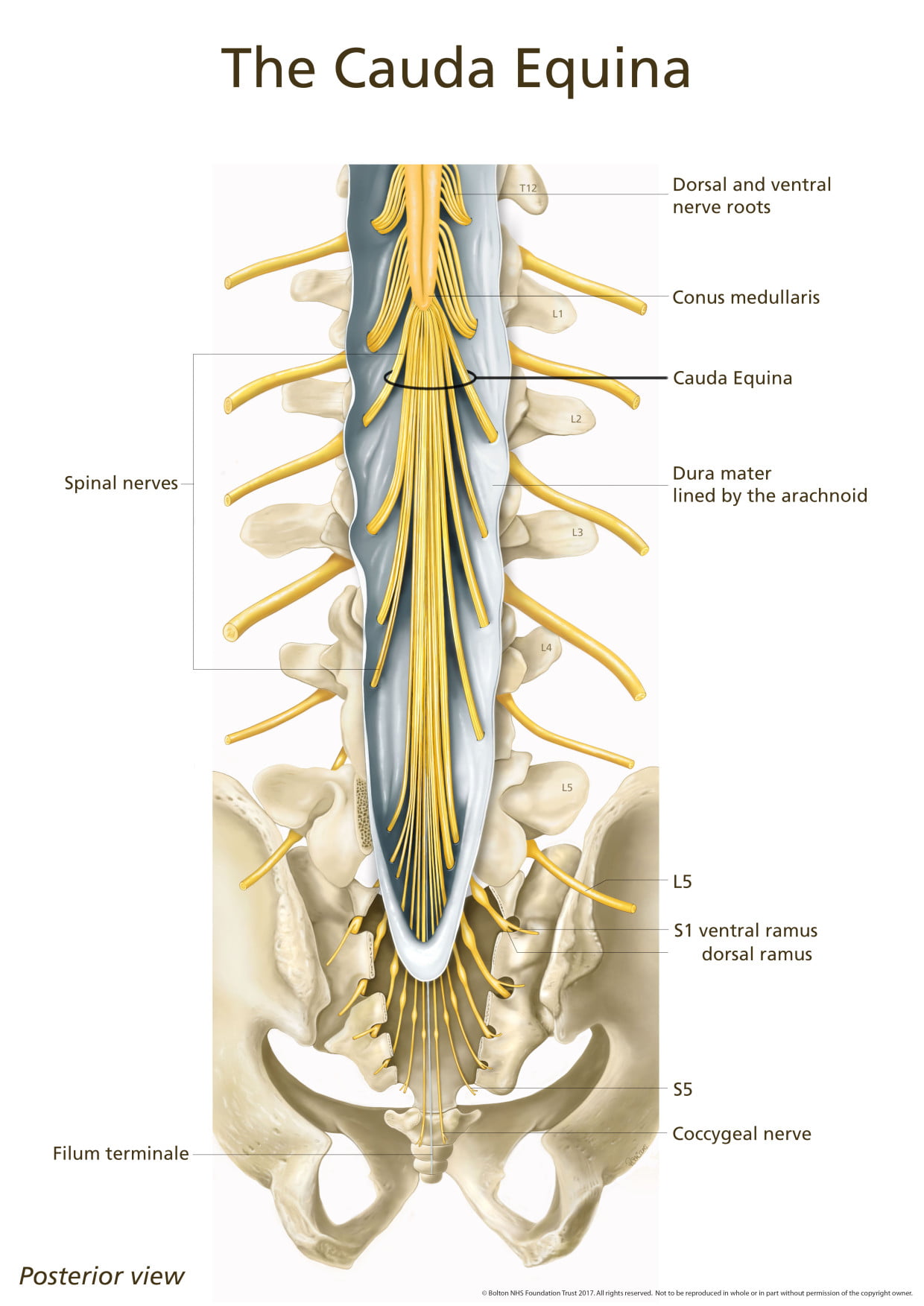

Recommendation 4: Clinicians should evaluate patients with persistent low back pain and signs or symptoms of radiculopathy or spinal stenosis with magnetic resonance imaging (preferred) or computed tomography only if they are potential candidates for surgery or epidural steroid injection (for suspected radiculopathy) (strong recommendation, moderate–quality evidence).

Recommendation 5: Clinicians should provide patients with evidence–based information on low back pain with regard to their expected course, advise patients to remain active, and provide information about effective self–care options (strong recommendation, moderate–quality evidence).

| WARNING: Before following Recommendation #6, please review the Contra-indications to NSAIDS use. |

There are more articles like this @ our:

Recommendation 6: For patients with low back pain, clinicians should consider the use of medications with proven benefits in conjunction with back care information and self-care. Clinicians should assess severity of baseline pain and functional deficits, potential benefits, risks, and relative lack of long-term efficacy and safety data before initiating therapy (strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence). For most patients, first-line medication options are acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

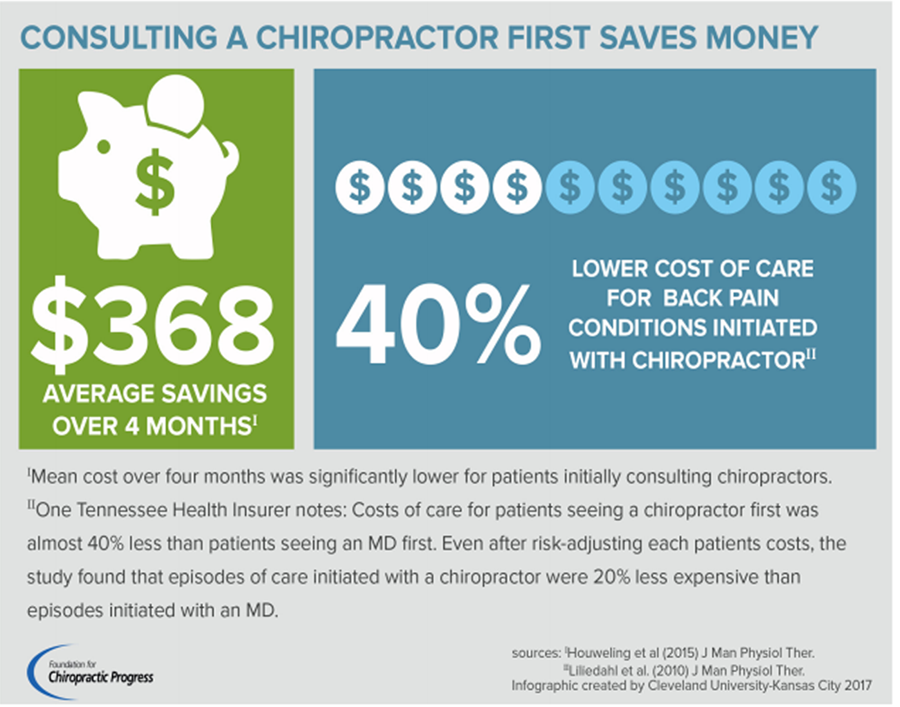

Recommendation 7: For patients who do not improve with self-care options, clinicians should consider the addition of nonpharmacologic therapy with proven benefits—for acute low back pain, spinal manipulation; for chronic or subacute low back pain, intensive interdisciplinary rehabilitation, exercise therapy, acupuncture, massage therapy, spinal manipulation, yoga, cognitive-behavioral therapy, or progressive relaxation (weak recommendation, moderate-quality evidence).

Introduction

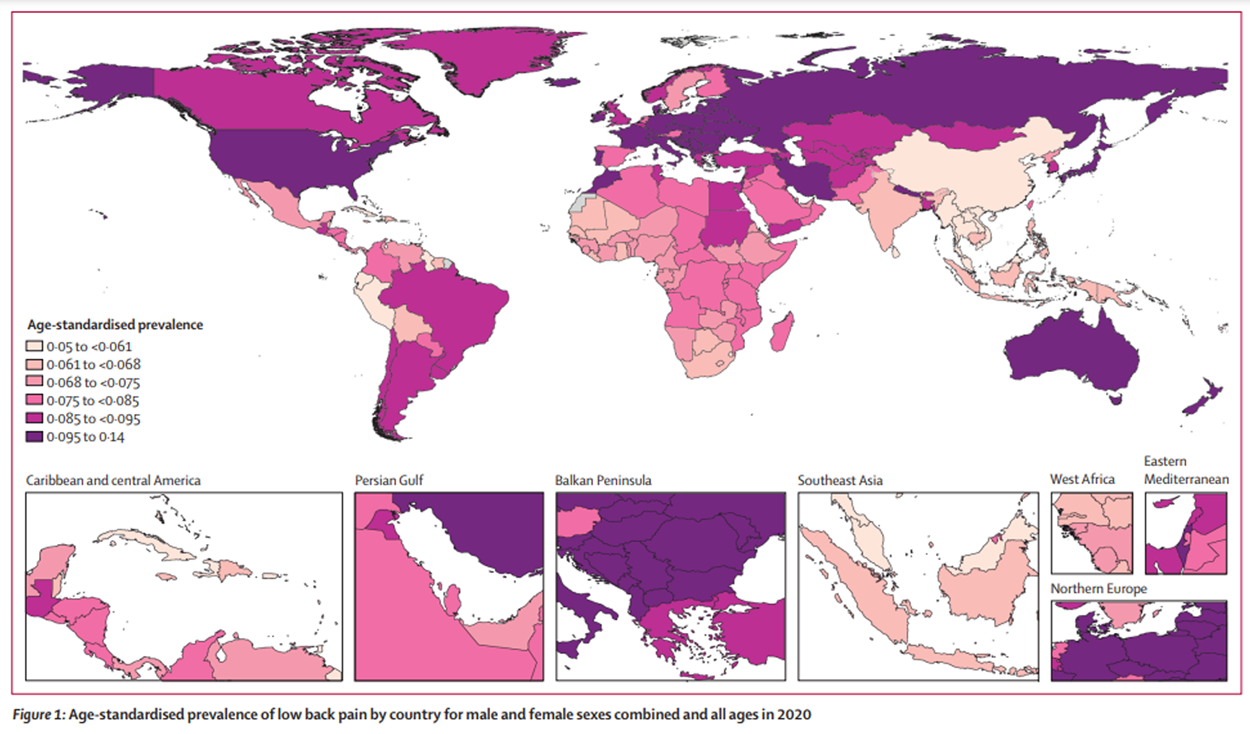

Low back pain is the fifth most common reason for all physician visits in the United States. [1, 2] Approximately one quarter of U.S. adults reported having low back pain lasting at least 1 whole day in the past 3 months [2], and 7.6% reported at least 1 episode of severe acute low back pain (see Glossary) within a 1–year period. [3] Low back pain is also very costly: Total incremental direct health care costs attributable to low back pain in the U.S. were estimated at $26.3 billion in 1998. [4] In addition, indirect costs related to days lost from work are substantial, with approximately 2% of the U.S. work force compensated for back injuries each year. [5]

Many patients have self-limited episodes of acute low back pain and do not seek medical care. [3] Among those who do seek medical care, pain, disability, and return to work typically improve rapidly in the first month. [6] However, up to one third of patients report persistent back pain of at least moderate intensity 1 year after an acute episode, and 1 in 5 report substantial limitations in activity. [7] Approximately 5% of the people with back pain disability account for 75% of the costs associated with low back pain. [8]

Many options are available for evaluation and management of low back pain. However, there has been little consensus, either within or between specialties, on appropriate clinical evaluation [9] and management [10] of low back pain. Numerous studies show unexplained, large variations in use of diagnostic tests and treatments. [11, 12] Despite wide variations in practice, patients seem to experience broadly similar outcomes, although costs of care can differ substantially among and within specialties. [13, 14]

SOURCE: Read the rest of this Full Text article now!

Leave A Comment