Specific Potentialities of the Subluxation Complex

We would all like to thank Dr. Richard C. Schafer, DC, PhD, FICC for his lifetime commitment to the profession. In the future we will continue to add materials from RC’s copyrighted books for your use.

This is Chapter 7 from RC’s best-selling book:

“Basic Principles of Chiropractic Neuroscience”

These materials are provided as a service to our profession. There is no charge for individuals to copy and file these materials. However, they cannot be sold or used in any group or commercial venture without written permission from ACAPress.

Chapter 7: Specific Potentialities of the Subluxation Complex

This chapter describes the primary neurologic implications of subluxation syndromes, either as a primary factor or secondary to trauma or pathology, within the cervical spine, thoracic spine, lumbar spine, and pelvic articulations.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

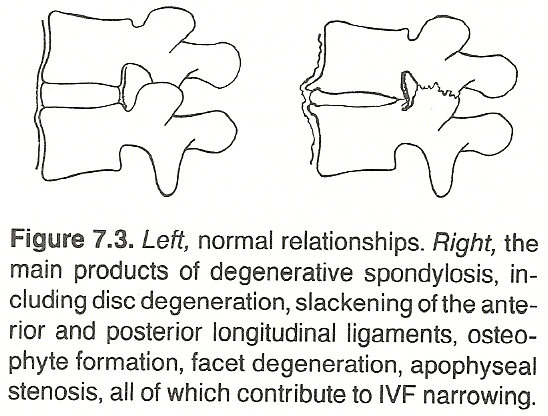

Studies reported by Drum, Hargrave-Wilson, Kunert, Burke, Gayral/Neuwirth, and others have shown that a subluxation complex, often leading to spondylosis, can effect a wide variety of disturbances that may appear to be disrelated on the surface. Most of the remote effects can be grouped under the general classifications of nerve root neuropathy, basilar venous congestion, cervical autonomic disturbances, CSF pressure and flow disturbances, axoplasmic flow blocks, irritation of the recurrent meningeal nerve, the Barre-Lieou syndrome, and/or the vertebral artery syndrome.

This chapter describes many causes for and effects of a spinal subluxation complex. In clinical practice, however, causes and effects are rarely found as isolated entities. Several factors will usually be involved and superimposed on each other.

Innervation of the Spinal Dura

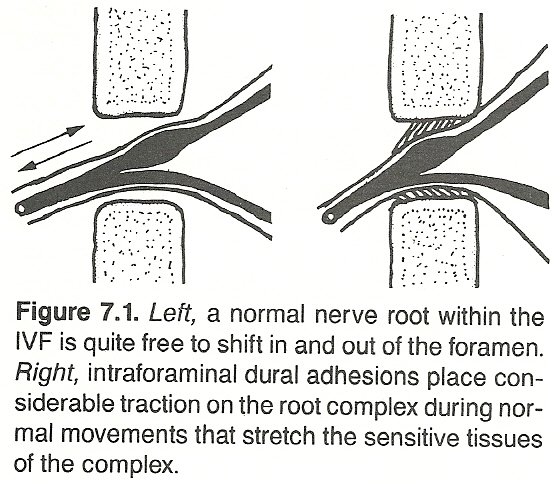

It has long been known that the spinal dura mater has an intrinsic nerve supply. Spinal meningeal rami are derived from gray communicating rami and spinal nerves. The spinal nerves contribute sensory fibers to the meningeal rami. Several meningeal rami enter each IVF, and most are located anteriorly to the sensory ganglia within the IVF.

Bridge found that these intrinsic nerve fibers reach the anterior surface of the dura by three main courses. Here the nerves divide into ascending and usually longer descending filaments that run longitudinally and parallel on the dural surface, and a considerable amount of nerve overlaps from adjacent segments. Finer filaments penetrate the dural substance where they subdivide.

Kimmel reported that most of these fibers penetrate the dura near the midline, while others enter laterally near the exiting spinal nerve roots. At each segment level, two or three nerves enter the spinal dura mater and contain only small nerve fibers. In contrast, Edgar/Nundy could determine no definitive nerve endings, but the nerves could be traced to the posterior aspect of the spinal dura. These observations help to clarify the wide distribution of back pain that is often found following protrusion of a single IVD.

Cervical Dura Attachments

Sunderland states that the nerve sheaths in the cervical region are not firmly attached to their respective foramina. Only the C4 C6 cervical nerves have a strong attachment to the vertebral column, and this is to the gutter of the vertebral transverse process. He believes that these observations have relevance to any local lesion that may fix, deform, or otherwise affect the nerve and its nroots to the point of interfering with their function, and they also may be important to traction ijuries of nerve roots.

Painful Irritations

The sympathetic nervous system, in conjunction with a sensory root compression or independently, plays a role in the interpretation of pain. Compression of the recurrent meningeal branch of the spinal nerves, for example, results in a wider distribution of pain and muscle spasm than the local pathology may indicate.

Many authorities attribute most lumbosciatic pains to IVD faults. The typical disc lesion is thought to produce restrictions in the dura mater during straight-leg-raising or neck flexion tests.

Cyriax believes that lumbago does not arise from tissue that has undergone degeneration (eg, myofibrosis) because the incidence of backache falls by two-thirds between the ages of 60 and 70 and has almost ceased by the age of 80. He attributes the pain to the impingement of discoid material on the dura mater or its root sleeve. He feels that the syndrome is initiated by an attack of internal derangement at a low lumbar IVD as the result of a momentary posterior displacement of a movable piece of intra-articular fibrocartilage. The prolonged subsequent pain is believed to be caused entirely by bruising of the dura mater.

(1) at the back of the IVD,

(2) laterally in the central canal,

(3) in the cauda equina,

(4) more laterally in the nerve canal, and

(5) posteriorly in the zygapophyseal joints.

Changes at these sites can produce dysfunction, disc herniation, instability, lateral entrapment, central stenosis. However, he does state that the pain from a disc lesion or stenosis may come from irritation and inflammation of the dura. The motor loss in these lesions may be attributable a reflex inhibition and vascular insufficiency rather than from nerve compression.

Nerve Root Compression/Irritation

| Review the complete Chapter (including sketches and Tables) at the ACAPress website |

I’ve always enjoyed reading Dr. Schaefer’s articles and books. However this particular exerpt “Specific Potentialities of the Subluxation Complex” from his text “Basic Principles of Chiropractic Neuroscience”, is just that – “potentialities” – there is no scientific validation!

Regardless of “potentialities” and definitions related thereto, are interesting, it is certainly an eon-removed from the original DD Palmer definition – you know, the one that all of the scientific world identifies us with – correction of “the” subluxation cures disease! I mean REAL disease!

Most chiropractors are aware of the the ACC definition of subluxation, which has been widely endorsed and has become somewhat of a “standard” for the chiropractic profession, I do have a problem with it:

First, the hypothesis that subluxation is some “complex of functional and/or structural and/or pathological articular changes that compromise neural integrity” is offered without qualification, that is, without mention of the uncertain, largely untested quality of this claim. The nature of the supposed compromise of “neural integrity” is unmentioned.

Secondly, the dogmatism of the ACC’s unsubstantiated claim that subluxations “may influence organ system function and general health” is not spared by the qualifier “may.” The phrase could mean that subluxations influence “organ system function and general health” in some but not all cases, or that subluxation may not have any health consequences. Although the latter interpretation is tantamount to acknowledging the hypothetical status of subluxation’s presumed effects, this meaning seems unlikely in light of the ACC’s statement that chiropractic addresses the “preservation and restoration of health” through its focus on subluxation. Both interpretations beg the scientific questions: do subluxation and its correction “influence organ system function and general health”?

Lastly, the ACC claims that chiropractors use the “best available rational and empirical evidence” to detect and correct subluxations. This strikes me as pseudoscience, since the ACC does not offer any evidence for the assertions they make, and since the sum of all the evidence that I am aware of does not permit a conclusion about the clinical meaningfulness of subluxation. To the best of my knowledge, the available literature does not point to any preferred method of subluxation detection and correction, nor to any clinically practical method of quantifying compromised “neural integrity,” nor to any health benefit likely to result from subluxation correction, regardless of whether “Joint fixation leads to abnormal changes, and the neurologic responses to it are unpleasant” (Classic “Post Hoc Ergo Proper Hoc” fallacy)..

I believe that whether chiropractors are actually treating lesions, or not, is a question of immense clinical and professional consequence. Resolution of the controversy will not be found through consensus panels nor through semantic tinkering, but through proposing and testing relevant hypotheses.

There is precious little experimental evidence available supporting the theoretical construct of the chiropractic subluxation. I believe it to be a legitimate , but untested hypothesis (in scientific terms). The evidence to date hardly supports the widespread notion among the chiropractic community that it is meaningful in human health and disease. It is this notion still prevalent today in chiropractic that brings ridicule from the scientific and mainstream health care communities. Over the years (last two decades, or so) many chiropractors preeminent theoretical constructs remains unsubstantiated and largely untested. There has been little if any substantive experimental evidence for any operational definition of the chiropractic lesion offered in clinical trials.

Notwithstanding strong intra-professional commitment to the subluxation construct and reimbursement strategies that are legally based upon subluxation, there is today no scientific “gold standard” for detecting these reputedly ubiquitous and supposedly significant clinical entities, and inadequate basic science data to illuminate the phenomenon . The chiropractic subluxation continues to have as much or more political than scientific meaning .

I don’t think the clinical meaningfulness, if any, of subluxation can be established by definition. The notion that subluxation is inherently pathological, perhaps because some dictionary equates subluxation with ligamentous sprain, does not mean that joint dysfunction merits clinical intervention

The magic and mystery of subluxation theories all too frequently direct the chiropractor’s attention to a search for the “right” vertebra, instead of addressing the legitimate question of whether subluxation (or any other rationale for manipulation) may be relevant in a patient’s health problem?

Many chiropractors bombard themselves and the public with subluxation rhetoric, but rarely hint at the investigational status of this cherished idea.

Hypothetical constructs involve tentative assertions about physical reality. They serve as essential tools in the development of science, and permit the empirical testing of the non-obvious. However, when the speculative nature of an hypothesis or hypothetical construct is not made obvious, an otherwise acceptable proposition becomes a dogmatic claim. Such is the history of subluxation in chiropractic.

The dogma of subluxation is perhaps the greatest single barrier to professional development for chiropractors. It skews the practice of the art in directions that bring ridicule from the scientific community and uncertainty among the public. Failure to challenge subluxation dogma perpetuates a marketing tradition that inevitably prompts charges of quackery. Subluxation dogma leads to legal and political strategies that may amount to a house of cards and warp the profession’s sense of self and of mission. Commitment to this dogma undermines the motivation for scientific investigation of subluxation as hypothesis, and so perpetuates the cycle.

It seems to me that as long as we as a profession rely on consensus statements concerning subluxation dogma as though it were validated clinical theory, the cultural authority we so desperately need to enter mainstream health care, will continue to elude us.

I stand by my assertions, that if we want to be included in mainstream health care, we must get rid of the subluxation theory, become part of state universities in terms of education, and develop chiropractic physicians who are evidence-based, ethical and upstanding…….we have a long road to hoe, with all respect to Dr. Schaefer!

Respectfully,

Peter G. Furno, D.C.

Indianapolis.

Dr. Furno

Thanks for your extensive post!

To reply, in brief:

Regarding your statement that: there is no scientific validation

You appear to have missed the extensive Bibliography at the end of the full chapter. There is only a short excerpt on our Blog, inviting you (at the bottom) to read the whole chapter.

http://www.chiro.org/ACAPress/Specific_Potentialities.html#Bibliography

Regardless, this material was written in the mid 1980s, so those references are quite dated by today’s standards.

I disagree with your suggestion that we should banish the word subluxation. The classic definitions (per Dishman, Lantz, Faye, Flesia and others) is a simple description of what happens when a joint becomes and remains fixated. That is the 5 Component Vertebral Subluxation Complex Model, as described on my “What is The Chiropractic Subluxation? Page” [1]

The recently revised Subluxation page now breaks the information down into it’s component parts: anatomic changes, degenerative and neurologic changes, and at the top of each section (in the yellow box) is some introductory comments from the in-depth article: “Basic Science Research Related to Chiropractic Spinal Adjusting: The State of the Art and Recommendations Revisited” [2]

I won’t attempt to reproduce, or condense all that research. You are welcome to review it at your leisure. The page, and the referenced JMPT article do a wonderful job of outlining what research has shown, and what information still needs detailing.

Your signature suggests that you are a DC, hopefully in practice. So, I ask you: do you adjust the spine? If so, what improvements do your patients report? Finally, does it really matter what you call that “thing you adjust” ??? It does to me.

Best wishes to you! I hope you enjoy the rest of our materials.

REFERENCES:

1. What is The Chiropractic Subluxation? Page

Chiro.Org ~ The LINKS Section

2. Basic Science Research Related to Chiropractic Spinal Adjusting: The State of the Art and Recommendations Revisited

J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006 (Nov); 29 (9): 726–761

Dr. Painter:

It seems to me that we are talking past one another! I am attempting a discourse based on present scientific fact, and you keep referring to outdated references from the 1980’s, as if that settles the issue! Regardless of how many “component parts” the subluxation is broken down into – a “complex of functional and/or structural and/or pathological articular changes that compromise neural integrity”, etc., etc., such is offered without qualification, that is, without mention of the uncertain, largely untested quality of this claim. The nature of the supposed compromise of “neural integrity” is unmentioned.

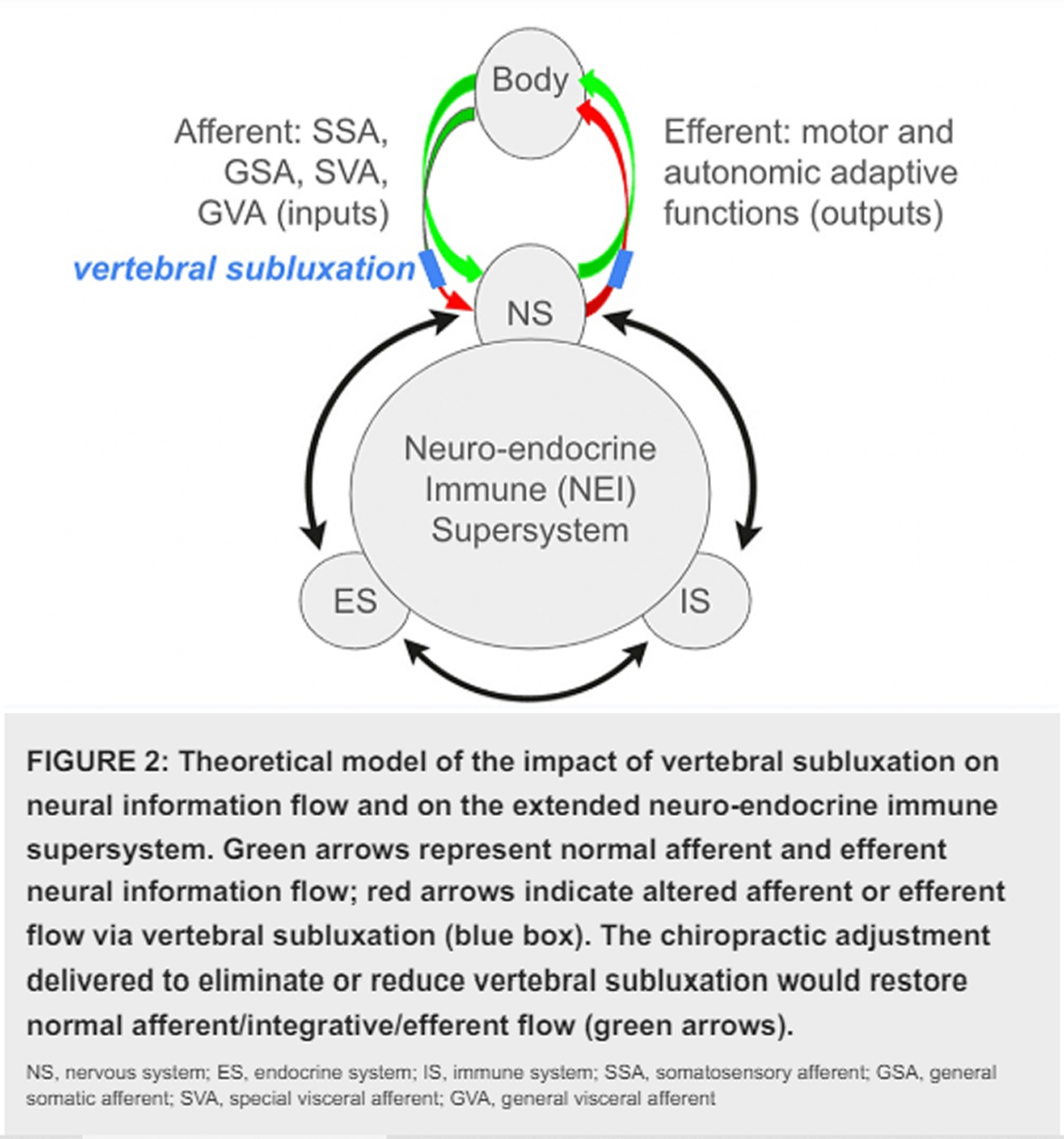

The original chiropractic subluxation theory proposed that misalignment of a vertebra obstructed nerve flow by pinching spinal nerves. Today, a subluxation is called a “subluxation complex” and is defined in many ways under more than 100 different names (such as a segmental dysfunction or a neurobiomechanical lesion). The Foundation for Chiropractic Education and Research defines a subluxation as “changes in nerve, muscle, connective, and vascular tissues which are understood to accompany the kinesiologic aberrations of spinal articulations.” Noting that such subluxations “may not be detectable by any of the current technological methods,” the proof of the existence of a subluxation is described as being reflected in reversal of “a variety of physiological phenomena.” In other words, if the patient gets better following a spinal adjustment, that is proof that a subluxation or some other spinal problem has been corrected.

Nonsense! Post hoc ergo proper hoc, I say!

It seems likely that many of the explanations this profession uses to explain the effects of a spinal adjustment, such as a reflex global response or an increase in white cell respiration, can also apply to other forms of everyday stimulation, such as an accidental bump, a deep massage, or a cold shower. But there is no reason to believe that such temporary physiological effects have anything to do with the cause and cure of disease, as postulated in the subluxation theory.

As we all know, there are 31 pairs of spinal nerves; 26 of these pass through movable vertebral segments. Five pairs of spinal nerves (accompanied by some parasympathetic fibers) pass through solid bony openings in the sacrum. There are an additional 12 pairs of cranial nerves which pass through bony openings in the base of the skull (including the 10th cranial parasympathetic vagus nerve, which travels down to supply visceral structures in the thorax and abdomen). The parasympathetic portion of the autonomic nervous system is well protected at its bony outlets and is not affected by slight misalignment of a vertebra, as suggested by the subluxation theory. Nor is it accessible to manipulation of the spine.

There is plenty of room for the passage of spinal nerves and blood vessels through the fat-padded foraminal openings between the vertebrae. It cannot be imagined that slight displacement of a normal vertebra will place pressure on a spinal nerve. This was proven conclusively almost 30 years ago years ago by experiments performed by Edmund S. Crelin, PhD, a prominent anatomist at Yale University. Using dissected spines with ligaments attached and the spinal nerves exposed, he used a drill press to bend and twist the spine. Using an ohm meter to record any contact between wired spinal nerves and the foraminal openings, he found that vertebrae could not be displaced enough to stretch or impinge a spinal nerve unless the force was great enough to break the spine. Crelin concluded: “This experimental study demonstrates conclusively that the subluxation of a vertebra as defined by chiropractic — the exertion of pressure on a spinal nerve which by interfering with the planned expression of Innate Intelligence produces pathology — does not occur.”.

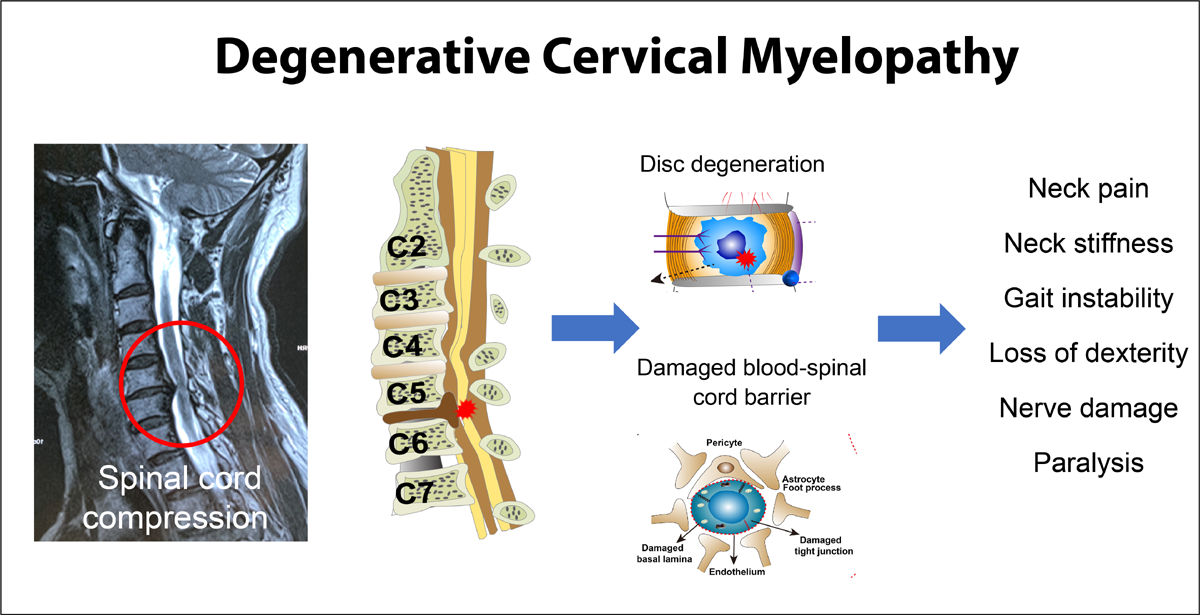

Spinal nerves are commonly pinched by bony spurs and herniated discs, causing musculoskeletal symptoms without any effect on visceral function. Even when the spinal cord is severed below the level of the fourth cervical vertebra, shutting off the flow of nerve impulses to spinal nerves, paralysis of musculoskeletal structures occurs from the neck down but the autonomic nervous system continues to maintain function of the body’s organs. If a transverse cord lesion occurs above the level of C5, however, disruption of parasympathetic nerve supply from the brain stem may cause death as a result of respiratory failure.

The mysterious and elusive chiropractic subluxation is obviously not the same as a medically recognized orthopedic subluxation, a partial dislocation, which causes pain and loss of mobility but does not cause disease or ill health. The truth is that slight misalignment of a vertebra has no effect on spinal nerves. When a spinal nerve is pinched, compressed, or irritated by a bony spur, a herniated disc, a thickened ligament, or some other pathological process, there may be pain, numbness, muscle weakness, and other symptoms in the skin and musculoskeletal structures supplied by the affected nerve. But this has no effect on visceral function or general health, and that includes stimulation of mechanoreceptors, nociceptors and/or proprioceptors. Injury to a spinal nerve may result in some autonomic disturbance in the portion of the skin supplied by the damaged nerve, but visceral functions are protected by a widespread, overlapping nerve supply from a number of sympathetic (autonomic) ganglia located outside the spinal column.

In view of the complex and fail-safe overlapping of the autonomic nervous system and the chemical reactions that occur in tissue fluids to maintain visceral functions, it becomes apparent that slight misalignment of a single vertebra is not likely to be a significant factor in the cause of disease. That the chiropractic version of vertebral subluxations may not exist at all is reflected in the fact that interexaminer reliability is low when chiropractors attempt to locate subluxations. Except in cases of gross misalignment caused by disc degeneration and other structural abnormalities, or in cases where chiropractors are using the Meric system, which simply assigns a certain vertebra to a specific organ or disease (used by 23.4% of chiropractors), few chiropractors find the same subluxations when attempting to relate a specific subluxation to a disease process.

I say again that the claim that subluxations “may influence organ system function and general health” is not substantiated by rigorous scientific method. As it stands currently, there is no compelling scientific evidence that the so-called subluxation effects health generally. Addressing the subluxation (fixation) has, indeed, been shown to effect MECHANICAL spine dysfunction with resultant amelioration of pain, but certainly NOT pathology of organ systems.

Surprisingly, you blythely pass over my contention that

much of chiropractic falls into the trap of the classic “Post Hoc Ergo Proper Hoc” fallacy. Your penultimate paragraph clearly reveals your misunderstanding of true scientific method – “….do you adjust the spine? If so, what improvements do your patients report?” Regardless of what the patient reports, such is NOT science!

If we are honest with ourselves, we will admit that the chiropractic vertebral subluxation complex is an historical concept but it remains a theoretical model. It is not supported by any clinical research evidence that would allow claims to be made that it is the cause of disease or health concerns.

The profession must realize that “magical thinking”, pseudo-science and fanatical dogma is part of the dark ages, and must be relinquished. A century of criticisms by political medicine, has only hardened many chiropractors’ attitudes. However, the purpose here is not to contain and eliminate the chiropractic profession, but rather to challenge dogmatic adherence to a hypothetical construct and to help to remedy the many problems that dogmatism has cost the profession. I believe that chiropractic should proceed as a first-class clinical science and art, a profession whose members appreciate and acknowledge what is known and what is not, provide patients with the best care possible given current knowledge, and resolve to extend the borders of scientific understanding in the interest of the public we serve.

Peter G. Furno, D.,C.

Indianapolis

P.S.

Yes, I am a practicing chiropractor of 43 years. Prior to chiropractic college I graduated from a real university with a B.S Mech anical Engineering. My education compels me to disregard “magical thinking” and the Post hoc ergo proper hoc fallacy!

Dr. Furno,

Not really. That old article listed the citations available at that time, which means you missed that in your zeal to comment. Of course they are dated. My first point was only about the fact that you seem to have missed them.

Your claim that there is no research: “uncertain, largely untested quality of this claim.” is based on what? You obviously have NOT looked at the Subluxation Page, because there is LOADS of materials that tie together the various components of this theoretical model.

You say it doesn’t matter “how many “component parts” the subluxation is broken down into”.

You also said: “If we are honest with ourselves, we will admit that the chiropractic vertebral subluxation complex is an historical concept but it remains a theoretical model. It is not supported by any clinical research evidence that would allow claims to be made that it is the cause of disease or health concerns.”

No arguement there. Almost all published chiropractic research has been funded either by our schools or by the FCER, while Medicine has been able to dip it’s beak into the $20 Billion YEARLY NIH funding. So, what’s most impressive is how much work has been done, while fending off constant attacks by organized medicine.

I am particularly concerned about your “cause of disease or health concerns” comment. Isn’t low back pain, neck pain or headaches a valid health concern? Are there not ICD diagnosis codes to diagnose those complaints?

You also quote DD or BJs original premise (bone on nerve, or the BOOP hypothesis) like that means something. No one I know accepts those ancient theories, they are hugely out of date now. It’s no more relevant to us than bleeding patients to get rid of evil humors does to medicine.

All the HYPOTHESIS of the subluxation is designed to do is to clarify OBSERVATION, to provide a framework for organizing thoughts and observations, to answer a question. And observation is the key to solution. That is the scientific approach.

All those comments from the ACC are background noise, or POLITICS … published by a Political Organization, interested in satisfying their constituents, so they can remain in POWER; it has no relevance to the reality of what we do daily in our offices, or what researchers are looking at in their labs.

In my “humble opinion” (hehehe) the only thing that matters is looking at the observations made by our researchers.

If you have read the writings of Chuck Henderson (Palmer College) as listed in the DEGENERATION section of the page you see the fixation component of subluxation being detailed.

His earliest work clearly demonstrates that

Ask yourself: What do you adjust on a regular basis?

If you have some compelling literature to refute Dr. Henderson’s findings, please list them.

You claimed earlier that there is no way to verify the presence of a subluxation. Yes and no.

We regularly use the cervical leg check (leg length changes when the head is rotated either to the right or left) to locate the side of “body rotation” of a fixed segment.

Then we use passive or active palpation to confirm that a particular segment IS fixed. Then we adjust it, by whatever technique we use. And by so doing, we reduce the liklihood of that segment degenerating further.

Call it what you will, but you feel fixation, you adjust, then you observe an improvement in function. The patient verifies that their neck moves easier, or their ROM has improved, or their headache is GONE. Gee, that sounds pretty cool to me.

What do you call that THING you adjusted? Historically, it was called a subluxation. Historically, we call what we do chiropractic. Out of respect to those who came before, I honor those terms.

Finally, I disagree that medicine disregards what we do because we use this dated term.

You were around during the pre- and post-Wilk era. You KNOW Organized Medicine spent decades and millions to destroy us BECAUSE we are competitors in an economic sphere that THEY wish to CONTROL. And the mis-information they sewed in the Public and their own rank and file remains, 25+ years later.

They continue to publish smear articles, masquerading in scientific journals, that claim SMT causes stroke, when numerous studies show that SMT forces are orders of magnitude less than the forces of normal end range ROM, and significantly less than the forces that can injure a normal, healthy artery. [2, 3]

So…Medicine is opposed to the IDEA that a DC provides an effective treatment, without drugs or surgery. All the rest is white noise BS.

REFERENCES:

1. Degenerative Changes Following Spinal Fixation in a Small Animal Model

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2004 (Mar); 27 (3): 141-154

2. Vertebral Artery Strains During High-speed, Low amplitude Cervical Spinal Manipulation

Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 2012 (Oct); 22 (5): 740–746

3. Microstructural Damage in Arterial Tissue Exposed to Repeated Tensile Strains

J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2010 (Jan); 33 (1): 14–19

….and that’s why we still have no cultural authority, no legitimacy and no trustworthiness – right, Doctor?! That’s why our market share continues to decline – right, Doctor?! That’s why we are generally considered cultists and magical thinkers – right, Doctor?!That’s why the tsunami of patients that are rightfully chiropractoic patients, presently under the control of mainstream medicine, will never have access to chiropractic care – right, Doctor?! While you and your ilk hang on to the metraphysical explanations of how things work, and completely ignore the Post hoc ergo proper hoc fallacy (or don’t even know what it is) as you go along your merry way, unconcerned about that bright light thundering toward you – the headlight of the locomotive of the era of evidence-based therapeutics – which is about to run you over!

And so lets have another “Pity Party” and point fingers! We’re pretty good at that, arn’t we?!

…actually, it’s folks like you, making broad editorial claims about our Profession, as though we are of one unified mind, that make folks wonder.

Do you deny the damage that decades of mis-information, sewn by the AMA and 20 other named medical organizations has wreaked? You sure seem to have ignored that in your commentary.

What will change things are economic forces. There are endless studies that show the cost effectiveness of chiropractic compared to medical care for the same complaints.

You are welcome to carry on, writing critiques on this Blog, assuming the role of some evidence-based savior. However, NONE of what you have said relates one iota to this article, or about the rest of the materials on our extensive website.

Please cite the materials on our site that you believe entail this magical thinking you are rattling on about.

Frank,

It’s been a while since I’ve been here. Thanks for keeping Subluxation real.