Comparison of Outcomes in Neck Pain Patients With and Without Dizziness

Chiropractic & Manual Therapies 2013 (Jan 7); 21: 3

B Kim Humphreys and Cynthia Peterson

University of Zürich and Orthopaedic University Hospital Balgrist, Forchstrasse 340, 8008 Zürich, Switzerland

Background The symptom ‘dizziness’ is common in patients with chronic whiplash related disorders. However, little is known about dizziness in neck pain patients who have not suffered whiplash. Therefore, the purposes of this study are to compare baseline factors and clinical outcomes of neck pain patients with and without dizziness undergoing chiropractic treatment and to compare outcomes based on gender.

Methods This prospective cohort study compares adult neck pain patients with dizziness (n = 177) to neck pain patients without dizziness (n = 228) who presented for chiropractic treatment, (no chiropractic or manual therapy in the previous 3 months). Patients completed the numerical pain rating scale (NRS) and Bournemouth questionnaire (BQN) at baseline. At 1, 3 and 6 months after start of treatment the NRS and BQN were completed along with the Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) scale. Demographic information was also collected. Improvement at each follow-up data collection point was categorized using the PGIC as ‘improved’ or ‘not improved’. Differences between the two groups for NRS and BQN subscale and total scores were calculated using the unpaired Student’s t-test. Gender differences between the patients with dizziness were also calculated using the unpaired t-test.

Results Females accounted for 75% of patients with dizziness. The majority of patients with and without dizziness reported clinically relevant improvement at 1, 3 and 6 months with 80% of patients with dizziness and 78% of patients without dizziness being improved at 6 months. Patients with dizziness reported significantly higher baseline NRS and BQN scores, but at 6 months there were no significant differences between patients with and without dizziness for any of the outcome measures. Females with dizziness reported higher levels of depression compared to males at 1, 3 and 6 months (p = 0.007, 0.005, 0.022).

Conclusions Neck pain patients with dizziness reported significantly higher pain and disability scores at baseline compared to patients without dizziness. A high proportion of patients in both groups reported clinically relevant improvement on the PGIC scale. At 6 months after start of chiropractic treatment there were no differences in any outcome measures between the two groups.

There are many more articles like this @ our:

Vertigo and Chiropractic Page and our:

Introduction

The complaint of neck pain is second only to low back pain in terms of common musculoskeletal problems in society today with a lifetime prevalence of 26-71% and a yearly prevalence of 30-50%. [1, 2] Most concerning is that many patients, particularly those in the working population or who have suffered whiplash trauma, will become chronic and continue to report pain and disability for greater than 6-months. [3-6] In terms of symptoms, dizziness and unsteadiness are the most frequent complaints following pain for chronic whiplash sufferers with up to 70% of patients reporting these problems. [7, 8] Apart from whiplash trauma, little is known about dizziness in the chronic neck pain population and much remains unknown about the etiology of chronic neck pain in general. [9]

Gender differences in reporting pain intensity is currently a topic of debate. Recent research suggests that females report more pain because they feel pain more intensely than males over a variety of musculoskeletal complaints. [10, 11] Furthermore, LeResche suggests that these differences may not be taken into account by health care providers, leading to less than optimal pain management for females. [12] However gender differences in neck pain patients with or without dizziness have not been described with respect to clinical outcomes over time.

Therefore, the purposes of this study on neck pain patients receiving chiropractic care are twofold:

- to compare baseline variables and the clinical outcomes of neck pain patients with and without dizziness in terms of clinically relevant ‘improvement’, pain, disability, and psychosocial variables over a 6-month period;

- to evaluate gender differences for neck pain patients with dizziness in terms of clinically relevant ‘improvement’, pain, disability, and psychosocial variables in a longitudinal study.

Methods

This is a prospective cohort study with 6 month follow-up. Ethics approval was obtained from the Orthopaedic University hospital Balgrist and Kanton of Zürich, Switzerland ethics committees (EK-19/2009) and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Patients

Consecutive new patients over the age of 18 with neck pain of any duration who had not undergone chiropractic or manual therapy in the prior 3 months were recruited from multiple chiropractic practices in Switzerland. All 280 members of the Swiss Association for Chiropractic were invited to participate in the study and 81 practitioners from both the German and French geographic regions of Switzerland chose to enrol patients. There were no set number of patients required from participating clinicians and all chiropractors were strongly encouraged during meetings and with frequent e-mail reminders to enrol all qualifying patients. Patients with specific abnormalities of the cervical spine that are contraindications to chiropractic manipulative therapy, such as tumours, infections, inflammatory arthropathies, acute fractures, Paget’s disease, cervical spondylotic myelopathy, known unstable congenital anomalies and severe osteoporosis, were excluded. Additionally, patients on anticoagulation therapy were also excluded.

Demographic and baseline data

Information provided by the treating chiropractor at the initial consultation included: patient age, gender, marital status, whether or not the onset of pain was due to trauma, whether or not the patient smokes, whether or not the patient was currently taking pain medication, duration of current complaint, number of previous episodes, whether or not the patient also complained of dizziness and the patient’s general health status (good, average or poor). This information was completed on a baseline information form. For dizziness, patients were asked to report if they currently experienced ‘dizziness’ which was described as feelings of ‘light-headedness’ or faintness or disorientation or unsteadiness or reduced postural and balance control that was related to their neck pain.

The eleven point numerical rating scale (NRS) for current neck pain ( 0 = no pain, 10 = the worst pain imaginable) and a separate NRS for current arm pain as well as the Bournemouth Questionnaire for neck (BQN) disability, were administered to the patient immediately prior to the first treatment by the office staff of each practice. The BQN is a multidimensional instrument covering 7 domains with each domain evaluated using an 11-point numerical rating scale (0 through 10). The seven domains include: (i) pain; (ii) disability (activities of daily living (ADL)); (iii) disability (social activities); (iv) anxiety; (v) depression; (vi) work, both inside and outside the home, fear avoidance; and (vii) locus of control. Each domain is evaluated independently on an 11 point scale with 0 indicating ‘not at all affected’ and ‘10’ indicating ‘maximally affected’. In addition to each domain score, the total score (maximum 70 points) is also calculated. The BQN has been translated and validated in both German and French with the seven domains as well as the over-all score having been shown to be more sensitive to change in a patient’s condition compared to other similar outcome measures. [13, 14]

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

Telephone interviews were conducted 1, 3 and 6 months after the first chiropractic treatment to collect the outcome data. The primary outcome of ‘improvement’ for both neck pain and the symptom of ‘dizziness’ was evaluated using the Patient’s Global Impression of Change (PGIC) scale [15] for the neck pain as well as a PGIC scale specifically concerned with dizziness. The PGIC is a 7 point scale ranging from ‘much better’, ‘better’, slightly better’, no change’, slightly worse’, ‘worse,’ and ‘much worse’. Only the responses of ‘much better’ and ‘better’ were considered clinically relevant improvement. [16, 17]

Secondary outcomes

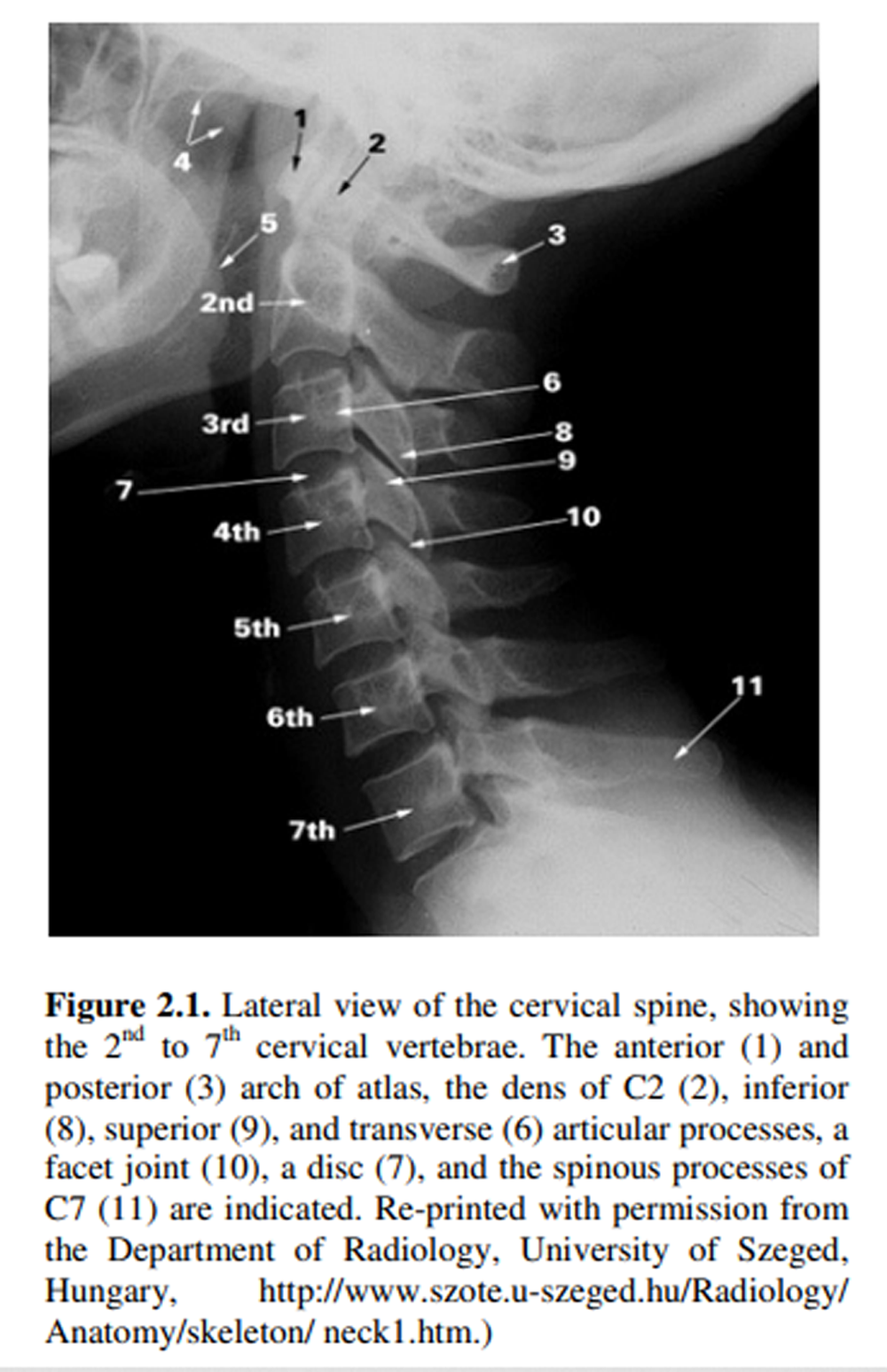

Additionally, data from the NRS (neck), NRS (arm), and the BQN were also collected as secondary outcome measures at 1 month, 3 months and 6 months after the start of treatment via telephone interviews (Figure 1). These telephone interviews were conducted by research assistants at the university hospital who were unknown to the patients.

Leave A Comment